Sustainability is all about finding new ways to protect the plant. You might work towards conserving natural resources or recycling more, but you should also think about how people can help the animal kingdom. Animals survived throughout history without depending on people, but now human pollution, infrastructure, and hunting habits have brought some of these species to approaching extinction. Our job is to ensure we are doing everything in our efforts to bring those animals back from the brink of extinction.

Dozens of animal species disappear from Earth every day. For each species that goes extinct, more become and remain endangered due to habitat loss, poaching, and climate change. These changes are primarily due to either human activities or climate changes. Congress passed the Endangered Species Act (ESA) and signed into law in December 1973. The act addresses the reality that hundreds of species were going extinct and that human actions attribute to many of the losses. Thanks to the ESA and countless efforts, several species have come back from the threat of extinction. Although animal extinction rates continue to rise, read on to find some of the animals brought back from the brink of extinction.

30. The Amur leopard population has risen from two dozen to 100 in the last decade after facing poaching and encroachment threats.

Did you know that the Amur leopard is one of the world’s most endangered wild cats? They have a thick yellow or rusty orange coat with long, dense hair. They can run up to speeds of 37 miles per hour. Barely holding on in Russia and China, the Amur leopard has an exhaustive list of hazards that has stood in the way of their future and put them on the brink of extinction. Some of the biggest threats that they faced included poaching, deforestation, inbreeding, and industrial encroachment.

By the mid-2000s, their population had fallen to just a few dozen left in the wild. However, collective efforts, including the successful Amur Leopard and Tiger Alliance, have helped bring up their numbers. Amur leopards have also successfully bred in captivity. However, that can cause eventual reintroduction problems for predators.

29. Although once on the brink of extinction, there are currently 60 Javan rhinos in a wildlife preserve.

Javan rhinos are confined to the island of Java in Indonesia after hunting and deforestation forced them from the rest of Southeast Asia. In addition to the hunting and deforestation, the Vietnam War also severely drove down the Javan rhino population as factors destroyed its once-thriving habitat. Today, only 60 Javan rhinos survive on a wildlife preserve at the tip of the island. Although we have made progress, there is still the risk of disease and inbreeding that can always be detrimental to this small population despite extensive efforts.

People have spotted a few other remaining populations off Java over the years; however, they are few and far between. The Javan rhino is not related to the five other rhino species, closely at least. The small size of the Javan rhino population is a cause for concern. The low genetic diversity and inbreeding can make it difficult for the long-term survival of the species.

28. Historically, giant otters were hunted for their pelts, causing a massive decline in their numbers.

Giant otters are among the few that remain in South America. They survive on fish; furthermore, people see them in groups hunting for fish together. People primarily hunted them for their pelts, which has been the largest contributor to their decline. However, it is not the only reason. Endangerment is also due to the disruption of their aquatic habitats. Due to the rivers and lakes being degraded and destroyed, the fish population is also negatively impacted.

Like many other animals on the brink of extinction, human decisions have contributed. The giant otters’ habitats have been negatively affected by pollution as well as fishing by humans. Fishing significantly reduces the food for the animals. The giant otters are also threatened largely by gold mining in the region, leading to mercury poisoning. The pollution has contaminated their home environment, making it difficult for them to survive and thrive.

27. The white-rumped vulture was once abundant but then was on the brink of extinction due to poisoning and lack of food.

One of the three critically endangered species of vulture, the white-rumped vulture has suffered a catastrophic decline across the Indian subcontinent. Diclofenac poisoning and lack of food led the white-rumped vulture to the brink of extinction. Since the 1980s, experts discovered that all but one percent of these birds were remaining. In India, ingested diclofenac from cow remains destroyed the majority of these birds.

People must study the breeding success of this threatened species and address the direct and indirect threats. Human encroachment and the rapid rise in agricultural sites contribute to their decline in food sources. The reduction of feeding opportunities impacted populations across Southeast Asia. Additionally, the diclofenac, which vets used on livestock, was a fatal medicine to the vultures. However, the use of diclofenac became banned in 2004.

26. There are only 12 vaquitas left today.

First discovered in 1958, the Gulf of California is home to one of the world’s rarest aquatic mammals and the smallest cetacean. The vaquita is a small porpoise whose population has seen a dramatic decline. Only five feet long, this porpoise has a gray body, and a pale or gray or white belly. It also has a dark patch around its eyes and dark patches forming a line from its mouth to its pectoral fins.

In 1997, there were 600 vaquitas alive, whereas today, there are only 12. The vaquita is a mammal that is smaller than humans. People scoop up these creatures in fishing nets. The practice of gillnetting for larger fish has intensely harmed the vaquita population. Gillnetting is a fishing method often used by commercial fishers. They also do not handle captivity well. This notion is terrifying because this means that the remaining population could be at risk soon.

25. Pangolins are primarily threatened by poachers who are after the meat and scales of the animals.

You can mainly find these nocturnal animals in forests and grasslands in parts of Asia and Africa. Their main threats are poachers who are after their meat and scales. In Vietnam and China, the meat of a Pangolin is considered a delicacy. People also use their scales in traditional medicines. However, there is no scientific evidence in today’s medicine to reveal that pangolin scales have any health benefits.

Nevertheless, over a million pangolins have been illegally poached in the past decade. In turn, this action further contributes to its extinction risk. Experts estimate that 100,000 are captured and trafficked every year. Pangolins have long sticky tongues that help them slur ants and termites. These animals are about the size of a house cat and can roll up into a ball when frightened. There are eight species of pangolin – four Asian and four African. The Asian species are critically endangered, while the African species are considered extremely vulnerable.

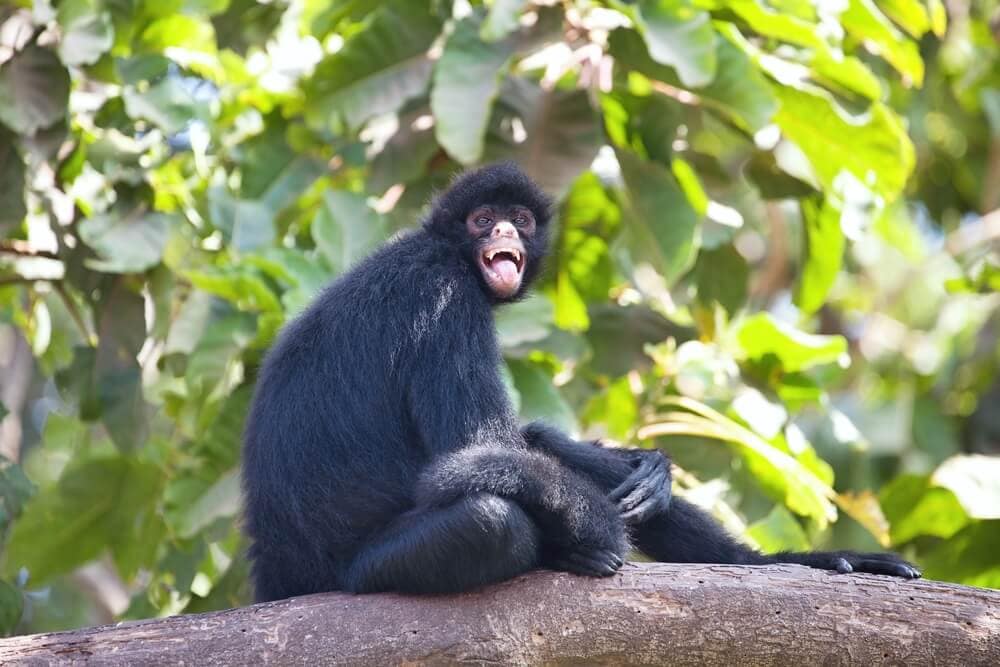

24. Peruvian black spider monkeys are threatened by hunting, fragmentation, and their homes’ destruction.

Over the past 45 years, the Peruvian black spider monkey population has declined by 50 percent. This fact is mainly due to hunting, fragmentation, and the destruction of their habitats. Their species is hunted locally for meat. Deforestation for cattle farming, agriculture, and mining has resulted in severe habitat loss. They spend the majority of their time in the canopy of the rainforest.

Since they prefer mature tropical forests and seldom venture into disturbed habitats, these monkeys are especially vulnerable to the effects of forest fragmentation. Eating mostly fruit, these monkeys are an essential part of the tropical rainforest ecosystem, playing a role in seed dispersal, allowing their forest environment to continue to grow and thrive. Peruvian black spider monkeys are known as red-faced or Guiana spider monkeys. You can find them in Bolivia, Brazil, and Peru. However, one of the seven species of spider monkeys is in Latin America.

23. The myxomatosis virus transmitted through rabbits contributed to the decline in the Iberian lynx population.

By 2005, the Iberian lynx population numbers had declined to around 100. One of the main contributors was the deliberate introduction of the myxomatosis virus. People introduced the virus on purpose to keep rabbit populations under control. Unfortunately, because Iberian lynxes don’t eat much else, myxomatosis consumption caused a rapid decline in their number. Also, infrastructure such as roads, dams, and railways contributed to some Iberian lynx loss.

Their fragile habitat is under threat from illegal farms and wells, mining, and gas extraction. In Portugal, there are organizations such as the National Breeding Center for Iberia Lynxes. With their tireless efforts, Iberian lynxes’ numbers have grown steadily, surpassing 400 last year. They also give the lynx more room to breed by creating new populations in other regions. In 2016, people released 37 captive-bred lynxes in reintroduction areas.

22. The Galapagos tortoise population quickly declined due to habitat destruction and excessive exploitation by humans.

While once numbered in the hundreds of thousands, the Galapagos tortoise population has drastically declined. Sailors and whale hunters massively hunted them because of their meat. As a result, several subspecies went extinct. Also, because of many predators, only a small number of hatchlings survive until adulthood. Their natural habitat was also cleared for agricultural purposes and further contributed to their lowering numbers.

In addition, the Galapagos tortoises are significantly threatened by introduced species to the islands, such as dogs and cats; these new animals prey on tortoises. Cattle, which compete for grazing vegetation, also threaten them. Fortunately, conservation efforts have been incredibly successful. One particular creature named Diego has managed to father 800 offspring and is still thriving even though he is older than 100 years.

21. Hunting for the European bison’s hide was the main threat to the species’ extinction.

The European bison is a hybrid between aurochs, domestic cattle descendants, and steppe bison. Also known as wisent, they were declared extinct in the wild around 100 years ago. The main reason for the European bison being on the brink of extinction was hunting. People hunted them for their skins and tongues and would leave the rest of the animals behind. Since all of the bison alive today come from a small surviving core group, there is a limited variety in their genes’ makeup. This notion makes the European bison susceptible to diseases, decreasing their life span and intervals between calves’ birth.

The bison are also vulnerable to similar diseases to domestic cattle. Although their presence in the wild disappeared, rewilding projects over the last 60 years have been extremely successful. There are now more than 3,000 European bison living in the world.

20. Saolas are a rarely-seen, critically endangered mammal threatened primarily by hunting, specifically from commercial poaching.

Found in Vietnam, saolas are an unusual cattle relative that most people never see. In fact, scientists have only seen saolas in the wild four times. Their main threat stems from commercial poaching in addition to some habitat loss. Poachers will set up thousands of wire cables, and the saolas are unable to free themselves. Although patrol teams have removed hundreds of thousands of wires, committed poachers continue to reset them.

Both male and female saolas have two parallel horns on their heads with white markings on their face. They are also indirectly threatened by insufficient attention to the conservation of their habitat. The continued fragmentation of their habitat is a result of human activity, such as road-building. The saola tends to avoid humans; they are solitary animals for the most part. Despite being related to livestock animals, saolas deal poorly with captivity and can only survive for a few months.

19. Darwin’s foxes have several threats. Habitat loss, hunting, and non-native species primarily threaten these carnivorous creatures.

You can find one of these foxes in Chile’s Nahuelbuta National Park. They are also on the island of Chiloe. Darwin’s foxes are dark in color with short legs. They are primarily active, mostly at twilight and dawn. These carnivores are considered an umbrella species. This fact means that protecting them and their temperate forest homes helps preserve the entire ecosystem. They face extinction because of habitat loss.

The greatest challenge to their survival is domestic dogs. Off-leash dogs sometimes can kill smaller foxes. Darwin’s foxes are also susceptible to contracting canine distemper virus, commonly carried by Chilean dogs. Several campaigns are underway to encourage responsible dog ownership. The drives also work towards limiting the entrance of dogs to protected areas known to house populations of Darwin’s foxes to aid in their population growth.

18. The Tapanuli orangutans population has decreased rapidly due to poaching and deforestation.

There are only around 800 Tapanuli orangutans left in the wild. Orangutans, along with humans, gorillas, and chimpanzees, are members of the great ape family. With so few left in the wild, any loss of habitat or disturbance can make the population too small to remain viable. Some parts of the Tapanuli orangutan’s range are still open for development, including mining and logging, further disturbing their habitat and species. In addition to habitat loss, they are killed as agricultural pests and hunted for the pet trade.

Although people have made conservation efforts to protect parts of the forest, there are still areas not covered. The illegal settling of migrants threatens even the areas that are protected. Tapanuli orangutans have low reproductive rates, which makes their populations highly vulnerable. Females give birth to one infant every three to five years, so these species can take a long time to recover from population decline.

17. The Malayan tigers face the constant threats of habitat loss and forest fragmentation—experts only as few as 150 Malayan tigers left in Malaysia.

People can find a tiger in a few tropical forested areas of Malaysia and a small chunk of Thailand. These tigers are special because they are rare. Although there are approximately 150 Malayan tigers left in the wild, only between 80 and 120 are breeding adults. Their two major threats are poaching and forest degradation. Poachers illegally hunt them for the traditional Chinese medicine market. Poachers will come from outside of Malaysia and set up encampments deep into the rainforest.

Additionally, the massive conversion of the rainforests to palm oil plantations has significantly reduced the tigers’ habitat. Tigers could move between the major jungles with forested corridors, but factors destroyed them. On the other hand, the expansion of logging roads into what were once isolated parts of the forest had made it easier for illegal poachers to explore areas that were once off-limits.

16. The most significant threats to kakapos are predatory animals such as large cats, stoats, and rats.

Kakapos are unique parrots because they do not fly. Instead, they walk everywhere. Their largest threats are predatory animals that eat the chicks and the eggs. Since parrots cannot fly, they are particularly at risk from predators with a keen sense of smell. Hunters also excessively targeted these birds for their skins and feathers, which rapidly contributed to their decline in numbers and only made things worse.

They also suffer from low fertility, so they are challenging to breed, limiting their population size. This concept is because they rear their young on the fruits of the native trees. These trees only fruit every two to six years, and kakapo only breeds on those occasions. During the years between, the kakapo’s natural diet consists of coarse leaves, grasses, and herbs, which lack adequate nutrients for rearing chicks. Efforts, such as the Kakapo Recovery Program, have helped the species make a gradual comeback.

15. The Arabian oryx remains vulnerable to illegal hunting, overgrazing, and drought in the desert.

Although they once roamed the Middle East, the Arabian oryx has since been pushed back to an isolated area of Saudi Arabia. They eat mostly at night when the plants are most succulent after absorbing nighttime humidity. Humans have contributed to some of the Arabian oryx population’s threats, with hunting being the primary cause. Arab royalty organized massive hunts beginning in the 1930s that nearly obliterated the remaining populations.

In fact, in 1972, they were declared extinct in the wild. However, with efforts from the Phoenix Zoo and Operation Oryx, tasks were set up to establish a herd in captivity to prepare to reintroduce them into the wild. The oryx has made a successful comeback in both Israel and Saudi Arabia. There are now an estimated 1,220 wild oryx across the Arabian Peninsula, in addition to between 6,000 to 7,000 in semi-captivity.

14. Sumatran elephants battle many problems like habitat encroachment, deforestation, and poaching.

Sumatran elephants have experienced one of the highest rates of deforestation within the Asian elephant’s range. Different factors destroyed almost 70 percent of the Sumatran elephant’s habitat in one generation. While they typically have smaller tusks, they are still enough to tempt poachers who kill the animals and then sell their tusks on the illegal ivory market. Only male Asian elephants have tusks, so every poaching further skews the sex ratio. This notion further restricts the breeding rates for the species.

Besides, the paper and oil industries, along with plantations, cause some of the most rapid rates of deforestation. Elephant numbers have declined by a shocking 80 percent in less than 25 years. Sumatran elephants feed on various plants and deposit seeds wherever they go, further contributing to a healthy forest ecosystem. They also share this lush forest habitat with many other endangered species, such as the Sumatran rhino, tiger, and orangutan.

13. Brown’s hutias have faced the changing region for decades, including major deforestation and habitat loss.

The Jamaican rodents were first followed by Indian groups that lived on the island before European contact. The Hellshire Hills, which Brown’s hutias inhabit, have faced significant deforestation and overhunting. As their natural habitats get destroyed, human interaction with the animals becomes a must. The Brown’s hutias are nocturnal foragers that will eat crops and damage tree roots in farms, quickly becoming a nuisance to the farmers.

Although people rarely see these animals, the evidence they leave behind in the form of damage is not inconspicuous. Frustrated farmers may then choose to retaliate or continue to hunt the creature. They are still used as a food source by the locals and are widely chased by dogs or caught in traps. The continued damage is significant enough for them to be considered endangered. Mongooses have also been introduced to the region and are partly to blame for the population losses.

12. In 1969, the Przewalski’s horse was listed as extinct in the wild after a perfect storm of events, including pasture competition with livestock, mining expansion, and overhunting.

Together, these activities, combined with some harsh winters, pulled the species towards extinction with only a few wild populations remaining. Zoos provided a critical safety net for the animal. At one time, there were only a few hundred horses in captivity, with none in the wild. All of these horses descended from just 12 wild-caught animals that poachers caught in the early 1900s. However, people successfully reintroduced them into the wild in Europe, Russia, China, and Mongolia.

The largest wild herd of Przewalski’s horses live in a national park in Mongolia, including some wild-born horses. They could be found in a family network with a dominant stallion watching over mares and their offspring in five to fifteen groups. While they have been captured and occasionally confined to zoos, people will not be able to tame Przewalski horses.

11. Ten years ago, 1,800 reported Yangtze finless porpoises, and currently, there may be as few as 500.

The Yangtze River, the longest in Asia, used to be one of the only two rivers around the globe that was home to two different dolphin species – the Yangtze finless porpoise and the Baiji dolphin. However, in 2006, the Baiji dolphin was declared functionally extinct. The Yangtze finless porpoise population has rapidly declined due to wide-scale infrastructure projects on the river. Also, industrial pollutants have affected the ecosystem of the river downstream. The contaminants, combined with fishing and boating activities, drove the baiji dolphin to extinction.

Pollution is another major, long-term threat that also hinders the animals’ sonar. This action impacts their feeding, and many are also wounded and die because of ship strikes. Overfishing has caused a considerable decline in the porpoises’ food sources. Other human activities such as dam building and land reclamation have contributed to large-scale habitat loss.

10. Increased logging and climate change have impacted the Vancouver Island marmot’s ability to survive and thrive.

The Vancouver Island marmot is an excellent example of how small animals can contribute to and build ecosystems. While they spend most of their time burrowing underground to starve off predators, they act as seed dispersers. In addition to their own cover, smaller animals and insects utilize their complex burrow systems for protection. However, their predation rates are incredibly high. The majority of their yearly deaths come from predators like wolves, cougars, and golden eagles.

With increased logging, the marmots have fewer places to hide, making them more vulnerable to predators. Females produce few offspring in these areas. The shift in climate change also hinders the animals’ ability to grow their population. With the increase in warmer temperatures, Vancouver Island marmots spend less time hibernating in safety which makes them more vulnerable to predators such as cougars and wolves. Efforts are being made for ongoing conservation breeding and release to increase marmot numbers and maintain genetic variability.

9. Dutch and English settlers almost hunted the white rhino to extinction. However, more recently, poaching has been a significant threat to the species.

White rhinos are the second-largest land mammal. In 1900, 20 remaining southern white rhinos were remaining on a reserve in South Africa. Over the decades, their numbers gradually increased. By the 19th century, settlers killed the rhinos for both meat and sport. People almost hunted them to extinction before the government took note and started to protect the remaining rhinos. While the government implemented action, the southern white rhinos still have illegal poaching threats for their horns.

Ground-up rhino horn is still in demand in traditional Asian medicine; people use carved horns to make ceremonial daggers. The southern white rhino is particularly vulnerable to poaching because they are relatively unaggressive and live in herds. As human populations continue to spread, they also suffer from habitat loss as more land develops around them.

8. Infrastructure development and hunting have primarily impacted the giant panda population.

Severe threats from humans have left only 1,800 pandas in the world. Giant pandas are considered an umbrella species. In other words, when pandas are protected, we are also invariably protecting other animals that live around them. China’s Yangtze Basin region has the panda’s primary habitat. Giant pandas live mainly in temperate forests high in southwest China mountains, where they subsist almost entirely on bamboo. They must eat around 26 5o 84 pounds of bamboo every day, depending on what part of the bamboo they are eating.

However, infrastructure development, such as dams, roads, and railways, have isolated panda populations. This truth prevents them from finding new bamboo forests and potential mates. The loss of their habitat also reduces their access to the bamboo they need to survive. In the past, poaching has been an issue. Although its impact has declined after enacting the Wildlife Protection Act, pandas still sometimes get accidentally caught in snares set for deer.

7. Ili pikas are small mammals that are native to the Tianshan mountain range in China. There are less than 1,000 total ili pikas.

Global warming has severely impacted this tiny mammal’s habitat. Ili pikas are endangered mammals that are closely related to rabbits and hares. People first discovered this animal species in 1983, and individuals say they barely see them since. Due to rising temperatures, glaciers have receded, and the altitude of permanent snow has increased in the mountains. This notion has forced the pikas to retreat to mountain tops gradually. People initially found them at elevations between 3,200 and 3,400 meters.

Currently, they have reverted to heights of 4,100 meters. Soon, there will be nowhere for these creatures to go. They also face threats from livestock and air pollution. As a solitary animal that is not very vocal, ili pikas cannot alert each other if predators are near. The combination of predators, pollution, and climate change may be too much for them to withstand.

6. Hawksbill sea turtles are threatened by the loss of nesting and feeding habitats, fishery-related mortality, and pollution.

Their narrow, pointed beaks give these creatures their unique name: hawksbill. They are mainly found throughout the world’s tropical oceans and feed primarily on sponges. The Hawksbill sea turtle is a fundamental link in marine ecosystems and helps maintain coral reefs and seagrass beds. As they remove sponges from the reef’s surface, they provide better access for reef fish to feed. Hawksbills are especially susceptible to capture on fishing hooks or entanglement in gillnets.

However, sea turtles need to reach the surface to breathe, so those grabbed in the net risk drowning once caught. In addition, although various laws and acts protect them, there is a large amount of illegal trade in hawksbill shells and their products. They are highly sought after throughout the tropics for their beautiful brown and yellow carapace plates. People eventually manufacture them into -tortoiseshell items for jewelry and ornaments.

5. The most significant threats to the western chimpanzees are habitat destruction, poaching, and disease.

The western chimpanzee is the closest of the five subspecies on the brink of extinction, with only a few thousand surviving. The palm oil industry requires mass deforestation to grow plantations of palm trees. Their habitat quickly becomes vulnerable. In another location, where less than a thousand chimps remain, a gold mine has taken hold of the region and caused further destruction. It leads to the construction of towns to support the mines and the rise of gold miners. This action then commences furthering deforestation and poaching.

The main reason for poaching is bushmeat. Besides, as humans and chimpanzees come into more contact, chimps are increasingly threatened by disease. Due to genetic similarities, they can transmit many diseases. Since chimps have not been exposed to these diseases before, they do not have an immune system equipped to combat them.

4. There are less than 100 Sumatran rhinos in the wild. Poaching threatens their extinction.

As the only Asian rhino with two horns, the Sumatran rhino is the smallest of the rhino family; they live in isolated areas of dense mountain forests. Isolated in smaller areas, it can be complicated for them to find other rhinos to mate with. This idea further hinders the species’ ability to grow. They are easily recognizable because long hair covers their bodies. Their long hair helps keep mud caked to their bodies to cool them and protect them from insects.

Like many other rhino species, people hunt them for their horns. The growing consumer demand for rhino horn has driven the unsustainable increase in poaching. China and Vietnam are the two largest consumer markets for rhino horn. Due to the poaching, the Sumatran rhinoceros’s numbers have decreased by more than 70 percent in the last 20 years. Due to their low digits, there is little probability of breeding pairs encountering one another.

3. The Brazilian spix’s macaw’s primary habitat has been largely deforested.

The bird’s primary habitat, the Caraiba tree, has been primarily deforested, which leaves the macaws in a vulnerable position. Colonization and exploitation of the area destroy their habitat. The macaws rely heavily on the Caraiba woodland habitat for feeding and nesting. Their complete dependence on this specific habitat prevented them from expanding into surrounding territories. This concept means that any disruptions to their habitat can be detrimental.

The animals also faced the impact of trappers who removed nestlings and eggs from their nests to supply the illegal bird trade. As specialist trappers began to systematically remove chicks out of the nests and as nestlings became harder to come by, they captured the adults. There are roughly 100 in zoos and other preserves. Attempts to breed macaws have failed due to many of the birds being relating. The increase in inbreeding creates inviable offspring.

2. Hunting and inbreeding are the two main threats to the cross-river gorilla population’s survival.

Cross river gorillas live in a populated area by many humans encroaching on the gorilla’s territory. They have cleared the forests for timber and to create fields for agriculture and livestock. Poaching occurs in the woods, and even the loss of a few gorillas negatively affects such a small population. Although the hunting and killing of gorillas are illegal in Cameroon and Nigeria, the enforcement of wildlife laws is often lax. The level of hunting has declined significantly following conservation efforts. However, any amount of killing will have a tremendous impact on the population.

Additionally, there is a greater risk of inbreeding and a loss of genetic diversity because there are so few cross-river gorillas. Efforts to protect these endangered animals are focused on securing the forests that house them. Partners are working with Cameroon’s and Nigeria’s governments to create a safe area for the cross-river gorilla spans across these countries’ border.

1. Although the black rhino could double its numbers from 20 years ago to around 6,487 today, they are still critically endangered.

Between 1960 and 1995, black rhino numbers decreased by an incredible 98 percent. Since then, the species has made an astonishing comeback. Poaching and black-market trafficking continue to plague the species and threaten its path to recovery. Black rhinos have two horns, making these creatures a lucrative target for the rhino horn’s illegal trade. Political instability and wars have greatly hindered the rhino conservation work in Africa and have further increased poaching due to poverty.

Next to poaching, habitat loss contributes to the rhino population decline. Human activities like agriculture, settlements, and infrastructure development result in the loss and fragmentation of rhino habitat. This further increases the risk of poaching and inbreeding. The high population density in some sites leads to lower breeding rates and increases disease transmission probability. Smaller, isolated groups can also be prone to genetic impacts of inbreeding. Although the numbers have increased, people must continue concentrated efforts to save these animals.