From the ancient Roman astronomer Hypatia to the ancient Chinese chemist Fang, women have contributed to science from the earliest days of innovation. But many of their discoveries were ignored or dismissed during their lifetime because science was seen as the domain of men. In some cases, men took credit and received accolades for the work of their female collaborators. These are just a few brave, brilliant female scientists who overcame impossible obstacles to change the world.

Rita Levi Montalcini Set Up a Secret Lab After Being Barred From Research

As a Jewish woman born in Italy in 1909, Rita Levi Montalcini faced extraordinary barriers to success in science. Yet when she died at age 103, she was a Nobel Laureate whose discoveries in revolutionized neuroscience.Her father was resistant to his daughter pursuing education, as many fathers were at the time. She persisted and eventually graduated from medical school with the highest honors. But less than two years into her career as a research assistant, Mussoluni’s government banned Jewish people from working in professional careers. Refusing to give up her work, Levi Montalcini set up a makeshift lab in her bedroom to continue studying nerve cells in chicken embryos. This research was the basis of her most important and Nobel Prize-winning discovery in 1952.

But, before she made her historic discovery, her research was again interrupted when her family was forced to flee their home and go into hiding after the Nazis invaded their city. After the war, Levi Montalcini resumed her research, discovering nerve growth factor, a molecule necessary for nerve cell survival and tumor growth. She had an illustrious career spanning five decades, marked by multiple significant discoveries in neuroscience and cell biology. In 2001, she was appointed to the honorary position of Senator for Life in the Italian Senate. Of the many challenges that she faces, Levi Montalcini said, ”Above all, don’t fear difficult moments. The best comes from them.”

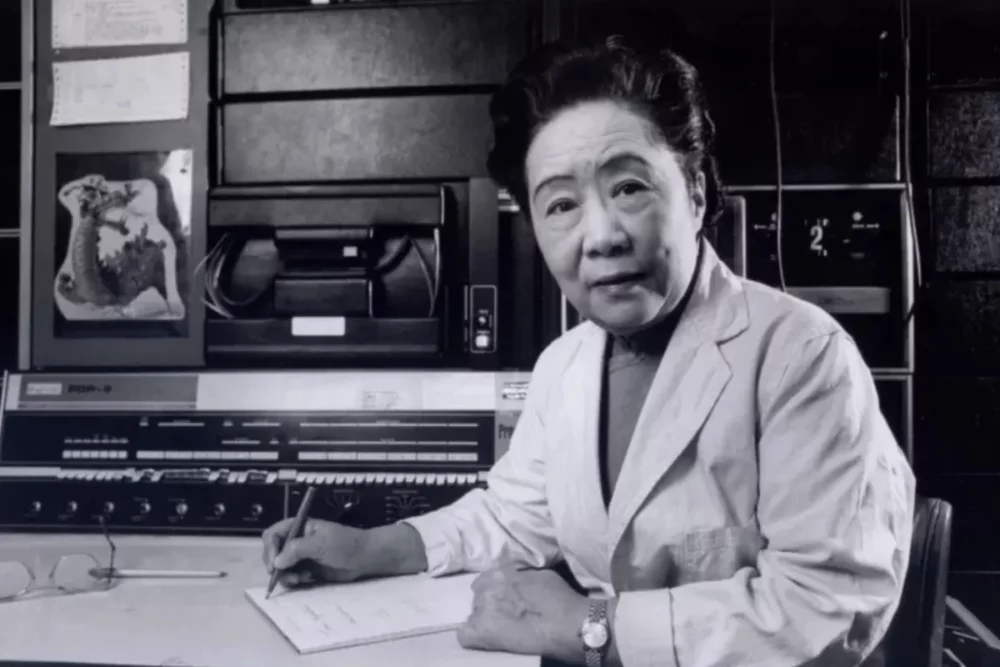

When Chien-Shiung Wu Found Closed Doors, She Opened Her Own

As a child in Jiangsu, China, Chien-Shiung Wu’s parents enthusiastically supported their daughter’s curiosity and academic pursuits. Unfortunately, she would find that the world was not always so welcoming. After excelling at school and university in China, Wu decided to continue her education in physics at the University of Michigan. But when she heard that the university reportedly wouldn’t let women use the front door of the student center, she changed her plans, heading to the Univerisity of Berkeley instead. At Berkeley, Wu quickly made a name for herself and became known as an exceptionally talented experimental physicist. But she still faced blatant sexism throughout her studies. An article about Wu’s accomplishments at Berkeley repeatedly references her physical appearance and calls the 29-year-old “a petite Chinese girl.”

Wu initially planned to return to China after completing her studies in the U.S. But World War II, the Chinese Civil War, and the rise to power of the dictator Mao Zedong prevented her from returning home and visiting her parents before their deaths. Still, she remained dedicated to her work, eventually developing the “Wu Experiment,” which proved an exception to a fundamental law of physics. Despite the experiment bearing her name, Wu’s male colleagues received the Nobel Prize for the groundbreaking research. Although denied a Nobel Prize, Wu received some of physic’s highest honors and is generally considered one of the most important figures in her field’s history, even earning the nickname “First Lady of Physics.” She was the first female physics professor in Princeton’s history and worked on the historic Manhattan Project.

Katherine Johnson Broke Race and Gender Barriers to Send Humans to Space

NASA mathematician Katherine Johnson had a perfectly ordinary start to life. But the path she took and the pioneering work she did would be anything but ordinary. Born in 1918 to a working-class black family in a small West Virginia town, Johnson was gifted at math, even as a very young girl. Black children were denied an education beyond middle school in her small town. Johnson’s family was forced to live in a city 130 miles away part-time so she and her siblings could attend high school. Johnson graduated high school at only 14 before enrolling in the historically black West Virginia State University. She excelled in every math class and graduated at 18 with the highest honors.

After college, Johnson worked as a teacher before marrying and focusing on raising her three children. It wasn’t until 1953, 16 years after she completed college, that she was recruited to work as a computer for the agency that would become NASA. Johnson and the other Black female mathematicians in the West Area Computing unit performed complex mathematical calculations that served as the basis for NASA’s space program. Her trailblazing work at NASA made the Apollo space mission to the moon possible. Johnson spent 33 years calculating trajectories for NASA space missions, but the significance of her work went unrecognized for decades. With the release of the 2016 book and movie Hidden Figures, Johnson finally began to get the credit she was owed for her unparalleled work.

Susan La Flesche Picotte Was the First Native American Woman Physician

Women healers were commonplace in Susan La Flesche Picotte’s Omaha tribe. But outside of her reservation, women’s path to becoming physicians was unfamiliar and mostly untravelled. After witnessing Indigenous people being denied medical treatment, Picotte decided to pursue medical training to care for her people. She attended a boarding school designed to assimilate Native American children into white culture before enrolling in the historically black university, Hampton Institute. Picotte graduated with honors and defied the more socially-acceptable expectations of marrying or becoming a teacher to study medicine at the Woman’s Medical College of Pennsylvania.

Despite some financial struggles and a break in her education to care for her family during a measles outbreak on their reservation, Picotte graduated at the top of her medical school class. She was the first Indigenous woman in the U.S. to become a physician. Keeping to word, she returned to the Omaha reservation, where she worked as a school physician and unofficial general practitioner for the community. During her career, Picotte was dedicated to several public health causes, including combating alcoholism, improving sanitation standards, and reducing the spread of tuberculosis. The latter was of personal importance to her, as the disease claimed the life of her husband and hundreds of others on the reservation. Picotte is remembered for her tireless work to improve the health of the Omaha people and for establishing the first hospital on a Native American reservation.

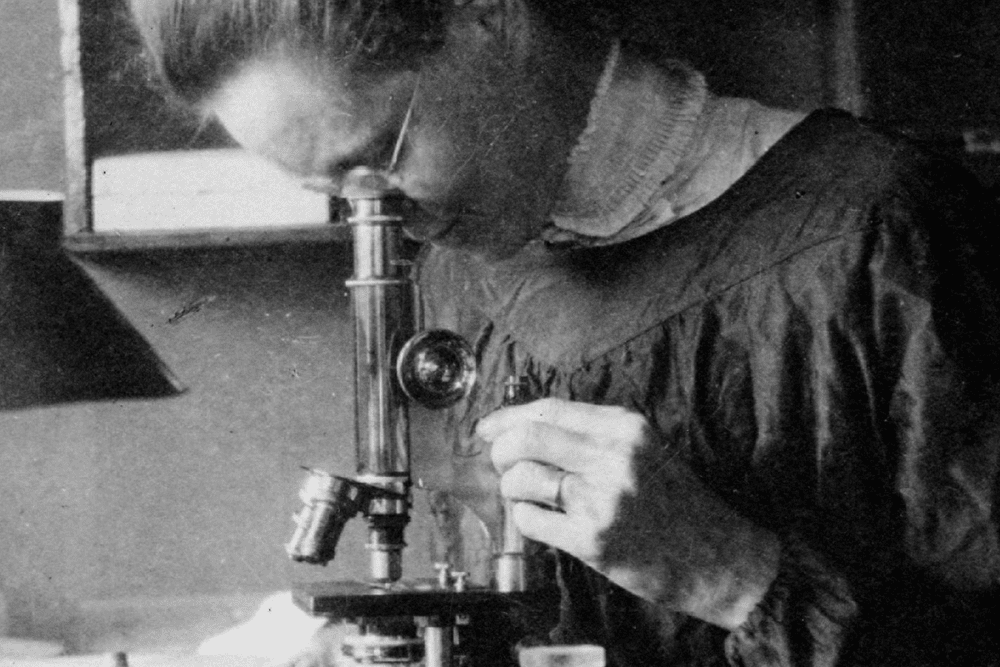

Undervalued in Her Time, Rosalind Franklin’s Legacy Lives On

Perhaps the most famous example of a female scientist who was denied her due by the scientific community, Rosalind Franklin’s many accomplishments are sometimes overshadowed by her collaborators’ slight. Born in London in 1920, her family described Franklin as an “alarmingly clever” child with an aptitude for math, science, and Latin. Her graduate research focused on the molecular structure of coal, and she discovered that it could be used to separate different kinds of molecules. This discovery is the basis of carbon filters used to purify water and air. Franklin. After earning her Ph.D., Franklin moved to Paris, where she became an expert in X-ray crystallography, a highly-specialized technique used to study the structure of molecules and atoms.

In 1950, Franklin began working in a lab alongside fellow biophysicist Maurice Wilkins, who treated her like an assistant rather than his peer. This caused ongoing tension between the two scientists. Unwayed from her work, Franklin developed a humidity-controlled camera to capture images of DNA that one colleague called “the most beautiful X-ray photographs of any substance ever taken.” With these images, Franklin first determined that DNA has a helical, or spiral, structure. Franklin’s work and images, along with the work of Wilkins, were instrumental in the final model of the DNA double-helix, constructed by James Watson and Francis Crick at Cambridge University. However, only the three men received recognition for the discovery. This is partly because Franklin’s role in the discovery was downplayed, particularly by Watson, and partly because Franklin died of ovarian cancer two years before Watson, Crick, and Wilkins were awarded the Nobel Prize in Medicine.

From the Margins Of Science, Mary Anning Uncovered Prehistoric Mysteries

Many people know that childhood tongue twister, “She sells seashells by the seashores.” But not everyone knows the woman who inspired was real-life fossil hunter Mary Anning, whose discoveries had a lasting impact on paleontology. Born to a poor family in the rocky beach town of Lyme Regis, England, in 1779, Anning survived being struck by lightning when she was only 15 months old. She was a bright child, despite receiving little formal education. Anning and her family collected fossils along the shore to sell to tourists for extra income. While fossil-hunting with her brother at age 12, the two discovered the skull of an ichthyosaur, a dolphin-like ocean reptile. Anning spent the next year slowly uncovering what turned out to be the first ichthyosaur skeleton ever unearthed.

Anning would make many incredible fossil discoveries during her life, including the first complete skeleton of a Plesiosaurus, a gigantic marine reptile. She became an expert in fossils, able to extract and identify countless delicate specimens. However, she was rarely credited for this work, even when other scientists used her specimens in their research. Early in her fossil-hunting career, some of her discoveries were disputed by men who accused her of faking her findings. With time, she became well-respected by scientists at the time. However, because she was a woman, she was barred from joining science societies, and the majority of her work went unpublished or uncredited.

Nettie Stevens Discovered Sex Chromosomes Only to Be Snubbed Due to Her Sex

Born during the first year of the American Civil War, Nettie Stevens’s dream of becoming a scientist was unusual. She was an excellent student and encouraged to enter the more “appropriate” teaching field after high school. Steven’s worked and saved her teaching wages for years until she could afford to enroll at Stanford University at 35. Seven years, she completed her college and graduate education and began her career as a genetics researcher at Bryn Mawr College. Stevens was interested in the genetic factors that make organisms male or female and studied the reproductive cells of mealworms. During her research, Stevens noticed that male and female mealworms have different chromosomes and that the presence of the smaller chromosome determined the sex of the worm.

The smaller chromosome would later be named the Y chromosome, while the larger was named the X chromosome. Stevens proposed that inheritance of the Y chromosome from the father produced males, and inheritance of the X chromosome produced females. Before her discovery, researchers believed that sex was determined by environmental factors before birth. Stevens’s discovery changed biology forever, but she was not initially recognized for it. Some in the field credited Edmund Wilson, a male geneticist who independently came to the same conclusion as Stevens. Eventually, the two were credited with the joint discovery of sex chromosomes, with Steven’s work being considered more complete and convincing. Tragically, Stevens died of breast cancer just a few after her groundbreaking discovery. She had a short but prolific career, publishing dozens of scientific papers.

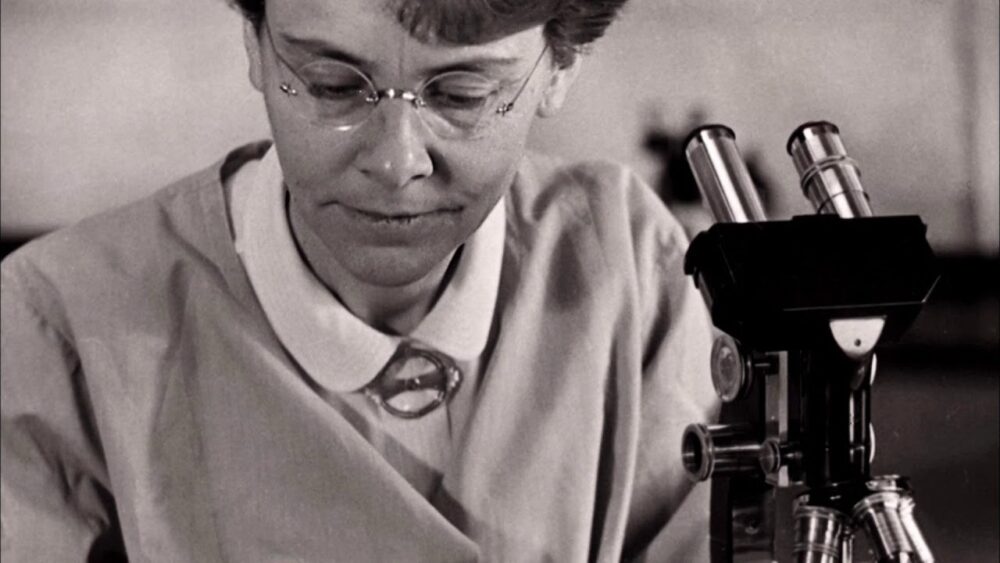

Nobel Laureate Barbara McClintock Was Dismissed as “Absolutely Mad”

Trailblazing genetics researcher Barbara McClintock spent much of her life fighting against people who doubted her. As a girl growing up in Connecticut and New York, she was described as an independent but shy child with a love of science. She wanted to attend college to study agriculture, but her parents were resistant. They believed that if their daughter gained too much education and independence, she would never settle down and marry. They weren’t wrong. McClintock never married. Instead, she revolutionized the field of genetics and became the first woman in history to win an unshared Nobel Prize.

McClintock studied genetics at Cornell University, where she helped pioneer the budding field of cytogenetics (the study of chromosome structure and behavior). She made several impactful breakthroughs at Cornell, but her most important discovery happened after she joined Cold Spring Harbor Lab. There she set about understanding what role genes play in the coloring of maize plants. Through this research, she discovered that genes could “jump” from one position to another with chromosomes. Her discovery wasn’t just cutting-edge; it defied all previous knowledge and conventions. Describing how other scientists responded to her research, McClintock said, “They said I was crazy, absolutely mad. But when you know you are right you don’t care.” McClintock’s discovery is now considered one of the most important in genetics history.

Biochemist Ruby Hirose’s Family Was Sent to Internment Camps

In the late 1930s, Ruby Hirose was immersed in groundbreaking research in antitoxins that would help pave the way for the polio vaccine a decade later. Her work at the University of Cincinnati gained considerable recognition in her field. It also spared Hirose the fate of thousands of other Japanese Americans who were forced into concentration camps during World War II. Unfortunately, her family was not so fortunate. Although there were internment camps across the country, most were on the west coast. In 1942, Hirose’s father and siblings living near Seattle, Washington, were sent to an internment camp. The fact that she had already left her hometown by the start of World War II is likely the only reason Hirose was not also sent to the camps and was able to continue her research.

Hirose’s research spanned many fields. She was one of only 10 women honored at the 1940 American Chemical Society meeting. Hirose studied allergies and worked on a method of using pollen to reduce sensitivity to the allergen. She suffered from a pollen allergy, which prompted her exploration of desensitizing the immune system by exposing it to allergens. This idea is the basis of modern allergy vaccines. Hirose also studied the protein involved in blood clotting and published a study on a medicinal plant used by the Cherokee and other Native American tribes to treat skin and digestive issues.

Marie Maynard Daly Defied the Odds to Discover How Food Affects Our Bodies

A popular book about the researchers who studied disease-causing bacteria sparked a life-long passion for science and medicine that led Marie Maynard Daly to her own transformative discoveries. She was encouraged in her interest by her father, whose dream of studying chemistry had been thwarted by financial constraints. As a black woman in the 1940s, Daly overcame dual discrimination to make an impact on her field. She graduated from college with honors before beginning her graduate education in chemistry. In 1947, Daly became the first black woman in the U.S. to earn a Ph.D. in chemistry.

Daly made many important discoveries throughout her long career. Her graduate research explored how our digestive system breaks down starch into sugar. In collaboration with microbiologist Alfred Mirsky, she helped explain how proteins are produced in the cell. Daly discovered that cholesterol can clog arteries, leading to high blood pressure and heart disease. She also studied the harmful effects of cigarettes on the cardiovascular system. Daly was an outspoken supporter of women and minorities in science. She founded a scholarship in her father’s memory to help prevent other Black students from missing out on their dreams.

Born into Poverty, Sau Lan Wu Has Three Career-Defining Discoveries

Most scientists dream of just one career-making discovery. In her over 50 year career, Sau Lan Wu has three—and she’s showing no signs of slowing down. Born in Japanese-occupied Hong Kong during World War II, Wu grew up in extreme poverty. Her mother encouraged her to find her independence through education. Wu received a full scholarship to Vassar College, where she decided to study physics like her hero Marie Curie. After completing her graduate education at Harvard, Wu launched her history-making career.

Wu’s most well-known work is her critical role in the 2012 discovery of the Higgs boson, a particle so foundational in physics that it was nicknamed “the God particle.” The particle was the last piece needed to complete the standard model of particle physics, which describes the building blocks of the universe. The search for the Higgs boson led to some of the most research advances in modern physics. Wu also helped confirm the existence of two fundamental physics particles. In 1974, she was part of the team that discovered the J/psi particle, which earned her advisor the Nobel Prize in Physics. Wu was also instrumental in discovering gluon, which is necessary to form protons and electrons. Now in her 80s, Wu continues her research at the University of Wisconsin and CERN.

Maria Merian Changed How the World Saw Insects

Before Maria Sibylla Merian began studying insects, many 17th-century scientists considered them “gross” and unworthy of study. But Merian knew better. A skilled artist and dedicated naturalist, she illustrated and described previously unknown traits of dozens of insect species. The stepdaughter of a still life artist, Merian began collecting and drawing insects, spiders, and plants at 13. Between 1675 and 1678, she published her three volumes of scientific illustrations. Then, in 1699, Merian went on a research expedition in Suriname to collect insect and plant specimens.

A few years after returning from the expedition, Merian published her greatest work, Metamorphosis Insectorum Surinamensium, establishing her as an authority in the field. Her book is considered one of the most important in the history of entomology, the study of insects. Merian’s remarkable drawings and detailed descriptions were the first virtual record of insect metamorphosis. This altered our understanding of insects and advanced the field of entomology. The 1980s renewed interest in Merian’s works, which remain among the greatest scientific illustrations ever.

Suffragette Mary Agnes Chase Risked Her Career to Stand Up For Her Beliefs

It would have been easy for Mary Agnes Chase, who fought hard for her position as one of the most distinguished botanists in history, to stay silent on political issues. Her critics certainly would have preferred that. But Chase was never afraid to stand up for what she believed in. She had a difficult start in life. Her father, an Irish railroad worker, died when she was a toddler, forcing the family to move to Chicago. She received little formal education, leaving school after elementary school. Her husband died just a year after they married. Still, she carried on in her career as an illustrator for the University of Chicago, the Field Museum of Natural History, and the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA).

Chase began studying the grasses outside Chicago and taking botany classes in her free time. She eventually began working with a fellow illustrator and botanist, Albert Spear Hitchcock, who attempted to give Chase money from his research grant to conduct her own study. The request was refused because Chase was a woman. Unfortunately, her work was not the only area where Chase felt this sting of sexist discrimination. In the 1910s, she became deeply involved the women’s suffrage movement, participating in protests and getting arrested several times. Although she faced threats of losing her job due to her political advocacy, she never wavered in her commitment. Chase mentored many female botanists throughout her life, published several highly-regarded works, and went on multiple international research expeditions, including a survey of Venezuela at 71.

Rachel Carson Defied Sexism and Launched an Environmentalist Revolution

When Rachel Carson wrote her revelatory book Silent Spring, she couldn’t have known how influential it would be. Her writing laid out the harmful effects of chemical pesticides. Then, she went a step further, taking the government and pesticide manufacturers to task for spraying poorly-regulated chemicals into the environment. Carson’s book almost single-handedly launched a global environmental movement against harmful industrial chemicals. Most impressively, Silent Spring and the movement it started were directly responsible for the U.S. banning use of the popular agricultural insecticide DDT, which causes seizures, tremors, and vomiting in humans.

Although Silent Spring was massively popular, it also drew accusations of radicalism and a lack of patriotism for daring to condemn the government. Her harshest condemnation came from the powerful chemical companies she criticized in her book. One critic dismissed her as hysterical and mocked her for being “scared to death of a few little bugs.” But Carson was no stranger to taking on a challenge. Born on a farm in 1907, she was a published writer by the age of 10. Her dream of being a zoologist was interrupted by the Great Depression. A few years later, Carson became the second woman to work for the U.S. Bureau of Fisheries. Throughout her career, she won many prestigious awards for her science writing and received a posthumous Presidential Medal of Freedom.

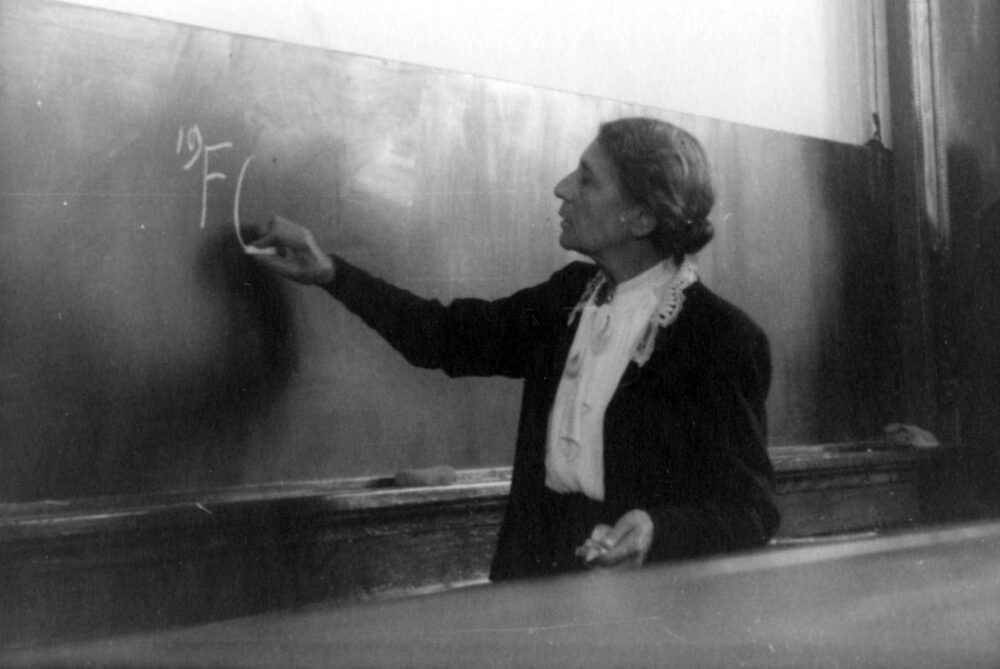

Lise Meitner Was Denied a Nobel Prize But Made It Onto the Periodic Table

Born to a Jewish family in Austria in 1878, Lise Meitner faced tremendous obstacles to her success in science. Her father, one the first Jewish lawyers to practice law in Austria, was a trailblazer in his own right. He hired tutors to support his daughter’s budding curiosity. However, when Meitner wished to study science at university, her father encouraged her to become a teacher instead. She passed her teaching certification but decided to enroll at the University of Vienna to study physics. Meitner was a brilliant student, completing her Ph.D. in Physics with the highest honors. After graduating, she struggled to find a research position. In 1907, she moved Berlin, where she spent the next 30 years of her career.

Meitner was not allowed to work in a lab in an official capacity in Berlin. Instead, she worked for several years without pay with chemist Otto Hahn. After their joint discovery of the radioactive element protactinium, Meitner got her own lab. She eventually became the first female physics professor at the University of Berlin. During this time, she began studying nuclear fission, a term that she coined. She was forced to flee Germany in 1938 due to Hitler’s rise to power. After arriving safely in Sweden, Meitner immediately continued her research. She was instrumental in uncovering the process of nuclear fission. But only her longtime collaborator Hahn received the Nobel Prize after downplaying her role in their research. Nonetheless, Meitner went on to become one of the most highly regarded scientists in her field and a tireless champion for women in science. In 1992, the 109th element on the periodic table, Meitnerium, was named in her honor.

Where Do We Find This Stuff? Here Are Our Sources:

17 Famous Female Scientists Who Helped Change the World

22 women of science who changed the world

Ten Historic Female Scientists You Should Know

22 Pioneering Women in Science History You Really Should Know About

6 Women Scientists Who Were Snubbed Due to Sexism