A lot has been made about body-snatching parasites in the world of entertainment for years. The question many might have is…how does that even work? How does a parasite not only get in your system but take over your body? To be clear, this article is not just about human bodies. Rather, it is more so about parasites taking over the bodies of animals. However, we will certainly be going over how some parasites could affect human beings. The reason you do not see them take over our bodies much if ever, is because we usually can communicate the issue to medical professionals. They can then help us remove them, or give us medication to do so.

Parasites can get into human bodies in a lot of different ways. Some parasites are inside water sources. If the water is not properly cleaned and filtered, one can get inside the body. They are also capable of being inside raw animal meat along with entering through open wounds. On top of this, when we reference body-snatching parasites specifically, we mean that one is capable of getting inside a body and affecting it negatively. This could result in a complete hostile takeover, or it slowly eats away at the body and lives inside as if it’s an organ. Now that you’re aware of all that, let’s discuss some of these body-snatching parasites!

Euchordodes

- Group: Chordodidae

Euchordodes are a family of horsehair worms known to scientists by the name of “chordodidae.” While one would assume a worm is not a big deal, you might need to make an exception for these little guys. Often found in New Zealand, many assume they just pop up around horses. That is not true nor untrue, it is just that it’s not that simple. In spite of being in a nation completely surrounded by saltwater all around it, this species is only known for being a freshwater parasite. This means that it would likely come across wildlife who drank from freshwater sources around the New Zealand territory.

From the map tracking resources, most of these parasites are located around Canterberry, Dunedin, & Southland. That means they’ll only be found in the warmest sectors of this nation, and likely not be spotted much in the northern portion. Stories about these parasites are horrific. They have been known to attach to insects that go on to commit suicide. The insects do not do this because they want to, the parasite takes them over to cause it. The Euchordodes quite literally eat everything inside the insect except only its vital organs. When it has enough, it takes over the insect’s brain to force them to kill themselves. Once they do, it just crawls out.

Paragordius tricuspidatus

- Group: Nematomorpha

The Paragordius tricuspidatus is a parasitic worm mostly known for using crickets as its host. During field examinations and testing, it was found that this parasite does indeed manipulate the behavior of the crickets they invade. It is likely done in a few ways, but mostly through chemicals. Interestingly, these worms are microscopic in their larval stage. They will eventually grow relatively large for a parasitic worm, between 4 to 6 inches. Usually, this happens when crickets accidentally eat eggs accidentally. Of course, the eggs are strategically placed by the edge of water sources like rivers where crickets can frequently be found.

Now that the microscopic version of the species is inside the cricket, it begins to feed on the inside of the body. Once it completely matures, the worm is naturally ready to get out and get into the water to reproduce. To do this, it takes hold of the cricket’s brain and forces it to leap into nearby water where the worm will exit the cricket’s body. Of course, this process of exiting is quite “graphic” to say the least. However, if the cricket is preyed upon by another species before making it, the worm can escape the host’s body pretty fast or through the predator’s digestive system.

Ichneumonid Wasp

- Group: Ichneumonidae

It is sort of surprising to see body-snatching parasites come from insects far larger than the worm versions. Yet that is exactly what you see with these parasitoid wasps. They have many names, and the version used likely depends on where you’re located or your knowledge of science. The Ichneumon wasps are quite vast and are potentially the most diverse parasitic species on the planet. There are at least 25,000 versions of this species known, which is insane when you think about it. Of course, scientists will tell you there is still very little we know about the species overall. From its distribution to evolution, and much more.

What we do know is that they only target holometabolous insects. These are insects that have four specific life stages: egg, larva, pupa, & imago. The latter of the four basically being adulthood. This means they pretty much only target specific insects and spiders, likely only those local to them. Of course, as one of the most infamous body-snatching parasites, these wasps actually attack the immature stages of a holometabolous’ life stage. Thus, likely within the egg or larva stage. This parasitic attack will eventually end the life of its host. Due to being an aid to biological control, humans believe this species serves a valuable role in our ecosystem.

Myrmeconema neotropicum

- Group: Tetradonematid Nematode

Compared to the other body-snatching parasites on this list, the Myrmeconema neotropicum is incredibly new. It is a nematode. To be fair, it is specifically a tetradonematid nematode, which is technically a worm. It differs from the others you might see in that it has to rely on a heck of a lot of luck to even come to pass. Get this, the nematode gets inside a South American ant which is then picked up and eaten by a bird of any kind. After the nematode passes through the bird’s digestive system, the eggs are sent out through the bird’s well, you can take two guesses here. From there, eggs are then picked up by ants and then fed to their larvae.

Now, the immature ant’s guts are filled with the eggs that then migrate to the gaster of the ant where they end up fully maturing. Once mature, the nematode will then reproduce inside the gaster. While males pass away soon after mating, females will hold eggs within themselves. As the ant becomes a young adult, its gaster actually becomes translucent. That is when you can see the red embryos from the parasite. In fact, this area only gets redder the longer this parasite remains inside it. Now, it looks like a red berry that birds will be attracted to. Once the ant goes out, it is then eaten by a bird. This, of course, starts the nematode’s lifecycle over again.

Glyptapanteles

- Group: Glyptapanteles sp.

This parasite has managed to get around quite well. It can be found in both Central & North America and even as far as New Zealand. Unlike other body-snatching parasites, the Glyptapanteles actually use their hosts as bodyguards rather than just feed on them. You should first know this is an endoparasitoid wasp that uses caterpillars as hosts for its eggs. A female wasp of this species will stick its oviposit into the caterpillar, which will then grow and feed like normal until roughly its 4th or 5th stage of development. Once it reaches this stage, around 80 fully grown larvae pop out of the caterpillar’s body to pupate. Yet at least one to two remain behind.

They are said to take hold of the caterpillar’s body/brain. The caterpillar then takes position near the cocoons of the pupae, will arch its back, and not move or feed again. It might spin silk here and there over the pupae but will thrash around violently if disturbed. Of course, this is essentially making a caterpillar into a forced bodyguard for larvae too small to last on their own. The caterpillar will soon die off due to not eating, but even when pretty much dead, it acts in defense against potential predators. These wasps evolutionary adopted this concept to stand a higher chance of fully maturing, and without it, mortality rates would be far higher.

Ribeiroia Trematode Flatworm

- Group: Ribeiroia

From ants to caterpillars, it makes sense for parasites to infect these mobile land animals. Yet the Ribeiroia Trematode Flatworm tends to favor infecting freshwater snails. Yet they will also go after other animals as secondary sources, like fish and the larva of amphibians. In fact, there have been studies to prove that these flatworms coming in so soon into the development of amphibians leads to limb malformations. Sometimes, they’ll use birds and mammals as hosts. Interestingly, the larger animals allow them the freedom to reproduce if multiple worms at least of two different sexes are in the same species.

Eggs will then end up in the intestinal tract of their host, which is then passed out of the feces of the host. This stuff usually ends up in water nearby, where the flatworm eggs develop fully within two to three weeks. Apparently, water temperature plays a role in the length. Once eggs hatch into miracidia, they will infect the first host that comes along. This is usually a snail more often than not. If they infect the snail, they will form into slow-moving worm-like parasites inside the snail’s reproductive tract. They’ll form inside the intestines or stomachs of others. From here, they pretty much force the actions of their host as they get bigger.

Braconid Wasps

- Group: Dinocampus coccinellae

The braconid wasp is pretty impressive, as they do not go after relatively small beings to help them out. Rather, this wasp goes after adult female ladybirds that are fully matured. They have become so well-known for this, the wasp species has now been referred to as the “ladybird killer.” Essentially, the wasp will use the ladybird as a zombie for a temporary period as a guard for its wasp cocoon. Of course, after the cocoon matures and the wasps are ready to come out, the ladybird is free to go. While roughly 25% of these ladybirds will recover from their wasp encounter, the rest tend to die after this occurs.

Of course, it is important that this ladybird remain alive as long as they take care of these eggs. While they do seek out females more often, there are times when male ladybirds are used. The eggs are planted in the soft underbelly of the ladybird, which can sort of make it appear that the ladybird is pregnant. They will then hatch within a week. Once the first instar hatches, the little wasps will use their large mandibles and move around other eggs as they begin to eat the fat bodies and gonads of the ladybird. This ladybird will go through all of this hell for up to 27 days. The bird is still able to feed, which is likely why it can survive the entire instar process.

Green-Banded Broodsac

- Group: Leucochloridium paradoxum

The green-banded broodsac flatworm is pretty incredible, and certainly one of the most impressive body-snatching parasites we’ve ever seen. Essentially, the broodsacs will find a way inside a snail. They will then move to the eyestalks, which actually draws attention to them for birds to pick them up. This is by design, as the bird is the broodsac’s primary host. Once inside the bird, eggs will be laid and released out through the feces. Before this can happen, the bird MUST spot the snail perfectly. How does the parasite truly manage this? They will infect the snail and manipulate its brain.

In fact, the parasite makes it want to go into well-lit places and place itself in higher vegetation. This will ensure the bird will see it easier than it would in darker territories. Moreover, getting it into higher vegetation means that the bird won’t have to search around on the ground from an aerial viewpoint for something to eat. It will easily spot the snail in a spot that is also very accessible. On top of this, the parasite forces the snail to sit in the same observation spot for at least 45 minutes to an hour. If a bird never comes for them, the parasite might leave the snail. It can then potentially survive for about a year after the encounter.

Tongue-Eating Louse

- Group: Cymothoa exigua

While this specific parasite does not infect humans, others like it will. This parasite is called a tongue-eating louse, and it is one of the creepiest body-snatching parasites known. We know members of its family pretty well as human beings. The louse is better known as “lice.” You likely experienced an issue with this when you were a kid, maybe even having to use a special shampoo and comb to get rid of them. They are essentially microscopic and hard to detect for us, yet the same cannot be said about this specific parasite when it comes to fish. When a louse spots a fish, it will attach to it usually through the gills.

Females will often go to the tongue while males will attach to the gill arches beneath or behind the female. They are actually pretty large for a parasite. Females can get a little over an inch long while males get about half an inch long. Once the parasite is inside a fish, it will sever blood vessels on its tongue. That results in the fish’s tongue falling off. It will then attach itself to the remaining portion of the fish tongue. The parasite literally then becomes this fish’s new tongue. Juveniles that first attach to gills are often males, but they eventually become female as they mature. Ensuring reproduction occurs consistently.

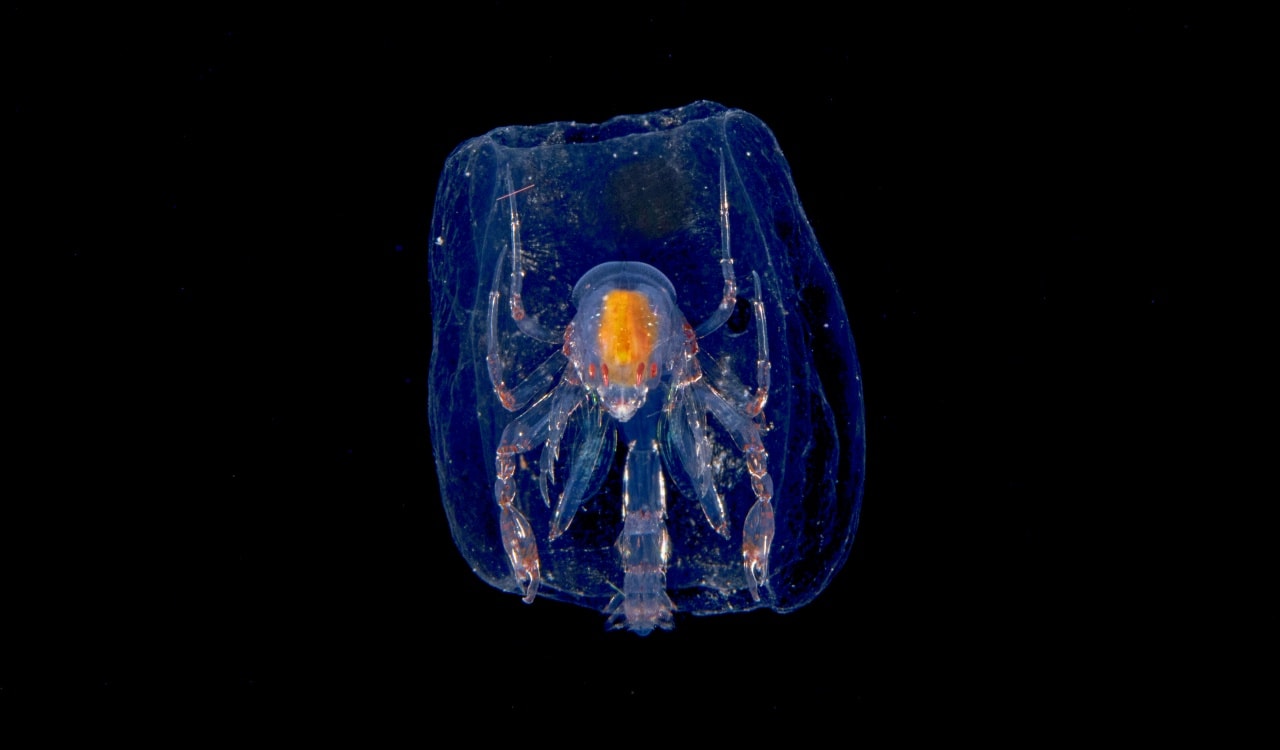

Phronima

- Group: Phronima Amphipods

While the Phronima can be found in most ocean territories except artic waters, they are not exactly referred to as parasites by some. In fact, scientists have often called them parasitoids. This still makes them a parasite, but parasitoids work a bit differently compared to simple parasites. They will often live inside their host, even allowing it to mature into an adult. Yet some might actually connect themselves to their host on the outside of its body. Of course, the Phornima like regular parasites can influence its host’s behavior.

That forces the host to be used exactly as the Phronima chooses, and will get exactly what it wants when it wants it. Once reproduction begins, the female will attack the salps of the water creature it is attached to. The female will use its mouth and claws to begin eating the animal on the inside and hollow out its gelatinous shell. It will then enter the barrel to lay the eggs inside, then propel the barrel through the water as larvae develop. That provides them with food and water on a regular basis as needed. The Phronima can do so much for such a long time to its host, making it one of the most notable body-snatching parasites on the planet.

Crab Hacker Barnacle

- Group: Sacculina carcini

With a name like the “crab hacker barnacle,” this specific parasite species must have a thing for crabs, right? Typically, it attaches to the green crab found all across Western Europe & North Africa. Most of the time when humans find a crab with this parasite, we tend to see it show up in the abdomen of the crab. By this point, it is usually too late to save the crab and certainly does not make it worth eating. A female crab hacker usually finds a crab host and will try to avoid any issues at first by crawling across the surface of the crab’s base. Since crabs are built pretty tough, the barnacle cannot get inside in its original form. It will transform into kentrogen.

This is sort of like a hook that allows it to force its way inside. Once there, it pushes out a sac on the underside of the crab’s abdomen. That sac will now take over the stomach, intestines, and overall nervous system of the crab in an effort to absorb all of the food the crab takes in. Of course, this also allows it to take over the crab and control its behavior. Due to needing the crab’s hard shell to remain, it attaches to the gonads forcing them to atrophy and preventing the molting process. If perhaps the parasite is removed, female crabs will regenerate lost ovaries but male crabs will have a sex change and will actually develop ovarian tissue.

Gall Wasp

- Group: Cynipidae

A lot of women may like the Gall Wasp because when it comes to reproduction, males are entirely unnecessary. These wasps are asexual and can produce eggs when they’d like to as they reach maturity. Yet what separates gall wasps from other parasitic creatures on our list is that they do not lay their eggs inside random spiders, caterpillars, snails, or any living mobile creature. They actually lay their eggs inside plants. Typically, they find oak trees where they will find a stem to pierce with their ovipositor. Normally, this area would be the place where stingers would be located.

However, gall wasps are not really like other wasps in this area. Once they implant the eggs inside the plant/stem, they will begin to puff up and swell. That will form a tumor-like growth we refer to as “galls.” Now you know where their name comes from. While this is still a body-snatching parasite, in that it does take over its host for a short period of time to get what it wants, it does not go after animals. On top of this, gall wasps are usually not harmful to humans either. Moreover, the oak tree does not have any problems after the eggs hatch and will continue on as if nothing happened.

Hymenoepimecis argyraphaga

- Group: Hymenoepimecis argyraphaga

This is one of the most fascinating body-snatching parasites we’ve ever seen. Of course, it is a wasp species that decides to use a host to help with its eggs like others on this list. Yet this Costa Rican wasp species uses a spider to help it out. Evolution is a crazy thing but also incredibly cool when you think about everything this wasp now realizes it must do to survive. Due to rain and potentially water in the wind being such a huge issue in Costa Rica, it can be tough for wasps to lay eggs and avoid weather issues. This is not even factoring in the massive amount of predators it must tangle with.

Thus, females will attack a strong, healthy spider by stinging it with their venom. From there, the female will use its ovipositor to dig around in the spider’s body to search for any potential existing eggs or larvae. If they find anything, it will be removed and then replaced by the wasp’s egg. That egg is then glued to the abdomen, usually hatching in 2 to 3 days. It will then feed on the spider from the inside, a few days later, it will then need to come out for further development. Thus, it will release a chemical that forces the spider to spin a specialized web to make a cocoon for it. Once they do this, the spider will be ended and consumed by the larva.

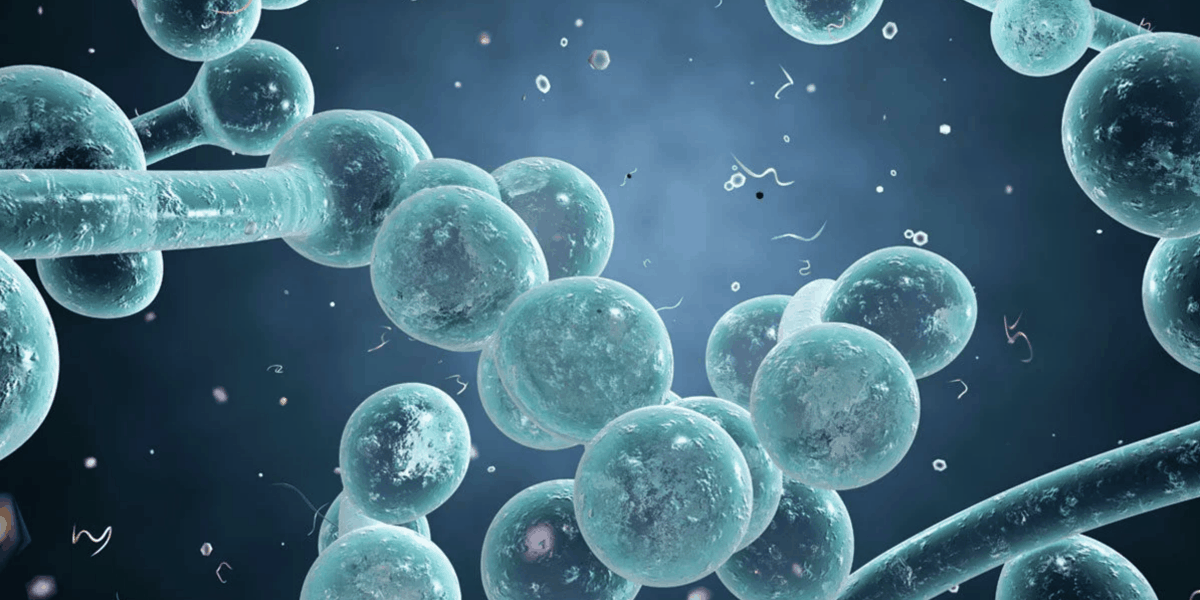

Candida Albicans Fungus

- Group: Candida

The Candida Albicans fungus is incredibly well-known in the medical community these days. It is known as a pathogenic yeast found in human gut flora. It is naturally detected more often in the gastrointestinal tract but also in the mouth. Roughly 40 to 60% of healthy adults will have it right now, some without knowing. But this can cause growth at times, which turns into an infection known as Candidiasis. During this process, the fungus becomes overgrown and begins to affect the human body in various ways. It is known that this fungus can cause severe brain issues if a person is not treated immediately upon detecting the infection.

In fact, a study was done on mice with this fungus and found that it caused Alzheimer’s Disease on top of various memory issues. While it does not attack the body in the same way a regular parasite might, the fungus itself is known to be just like a parasite. Once it becomes strong enough, it will begin to take over whatever it can to continue expanding. By showing it caused problems for the human brain, it appears that it is intelligent enough to somehow go after our central nervous system to try to make us forget about it being there. That shows a quest for survival in this fungus. In other animal species, just imagine how far it could go.

Lancet Liver Fluke

- Group: Dicrocoelium dendriticum

We have known of this parasite at least since 1819, but deep study and observations were done in the 1950s by C.R. Mapes & Wendell Krull to determine how it actually worked. We knew before this that the parasite enjoyed going after sheep. However, after further analysis, it was determined that the parasite originally attached itself to a land snail. Slime balls were coughed up by the snail, which then came in contact with sheep to transfer over. Due to how it works, several cattle species can be infected.

However, humans have also dealt with this Lancet Liver Fluke parasite before too. It tends to connect to the bile ducts of humans. The infection usually only remains in these areas and we have medication to stop them. Not getting help though can cause huge problems in the body, including an enlarged liver on top of skin rash issues too. While this might one of the many body-snatching parasites that exploit their host, due to the hosts they tend to target, the Liver Fluke often can pass through its host with mild symptoms. Yet humans might see the most severe issues from one, whereas cattle might not randomly die from it at all.

Polymorphus paradoxus

- Group: Polymorphidae

The Polymorphys paradoxes happen to be yet another parasitic worm species. They tend to make hosts out of local crustaceans as their intermediate hosts. These are hosts that act as carriers for a parasite until it can be seen by its final host. In this case, a crustacean will make itself known due to being controlled by the parasite that infected it. A bird will then see the crustacean, which it will then attack and consume. With it goes the parasite, now inside the bird where it will reproduce. There is often no guarantee that a bird will just see a crustacean randomly.

Like other body-snatching parasites, the Polymorphus paradoxes will try to ensure a bird of any type will spot it. Thus, it will essentially take over the brain of the crustacean to remove it from the water or potentially ensure it is in shallow territories. This will improve its odds to be seen by the bird. However, unique among body-snatching parasites, there are not a whole lot of markers that help you indicate the parasite initially. Sure, it is there and can be seen if we view the crustacean closely but the bird would not spot any special differences.

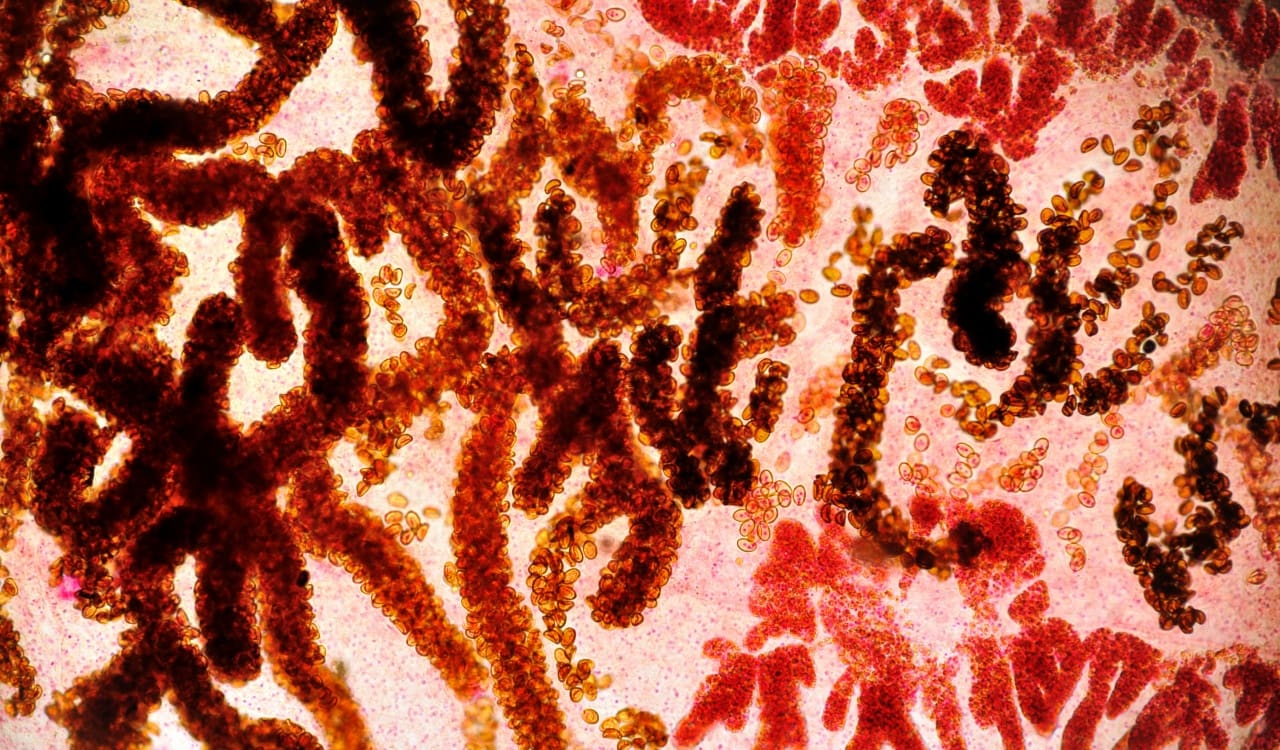

Ophiocordyceps

- Group: Ophiocordycipitaceae

You likely know the Ophiocordyceps parasite most from the Last of Us video game series. This is essentially what turned humans into zombies that everyone had to somehow escape before being infected themselves. It is a parasitic fungus that usually latches onto various insect species, and it is mostly found in Africa. In ants, it is said that Ophiocordyceps does some pretty impressive things. Once it attaches itself to an ant, it will force it to climb up and attach itself to the underside of a leaf. It could be on any plant or tree, as long as it is at least 25 centimeters off the ground.

Once the ant does this, its purpose has been served and the Ophiocordyceps will begin to grow. Due to being done with the ant, it removes itself from the species which makes the ant die. From here, the parasite begins to grow on the leaf. After a few days, deadly spores will come out. If humans come in contact with those spores, it infects people pretty easily. It can actually take over a person’s brain if they let it remain in their system long enough. But the big thing is that these are true body-snatching parasites that could potentially make a person insane if it remains inside us for too long. This could be why LU used it for their game series.

Entomopathogenic Fungus

- Group: Fungus

Usually, body-snatching parasites that come in the form of a fungus have a tougher time connecting to things. As they have to wait until something comes along so they can finally attach to it. The Entomopathogenic Fungus is asexual, therefore does not need a mate to reproduce. Therefore, the fungi will attach to an insect’s body externally at first. From there, it’ll form microscopic spores that will wait for the right temperature conditions to make their move. Usually, a warm and humid environment allows them to grow and colonize into the insect’s body.

Typically, it goes through the insect’s cuticle, bashing its way through using enzymatic hydrolysis. This will get it inside the body where it’ll be able to develop fundal cells inside the body cavity itself. Of course, when a fungus begins to develop like this, there is really no way an insect is able to survive. This is likely due to fungal toxins that spark up as it develops. Once that happens, the spores will then form not just inside the insect but also on the outside. Obviously, the right temperature conditions will need to be present for this to happen properly. Yet once it does, the growth occurs and the process will begin as another insect crosses its path.

Jewel Wasp

- Group: Ampulex compressa

We have referenced the actions of the Jewel Wasp a few times on Science Sensei over the years. It is hard to ignore what this wasp can do. Whenever one of these female wasps mature and is ready to have little wasps, they will find a cockroach to help with that. Once they spot the best one they can find, they will sting the roach directly in the brain. That will result in the roach being paralyzed for a brief period of time. This is more than enough time for the wasp to do as it needs. While the roach is out of it, the wasp takes it back to its burrow where they implant their egg. This is usually just one egg though.

From here, the roach is able to eventually come to and leave to go back to its own home. The wasp won’t protest the move, as it wants the roach to go back to its home. Thus, it’ll follow this cockroach back to where it is staying. Once inside, the wasp will then block the entrance and exit, effectively trapping the roach inside. At this point, the egg is growing and in three days, the larva will hatch and slowly begin to eat the roach from the inside. This mother wasp was able to control everything perfectly, giving it the best outcome while the baby wasp literally took over the body. Making it one of the most notable body-snatching parasites in the world today.

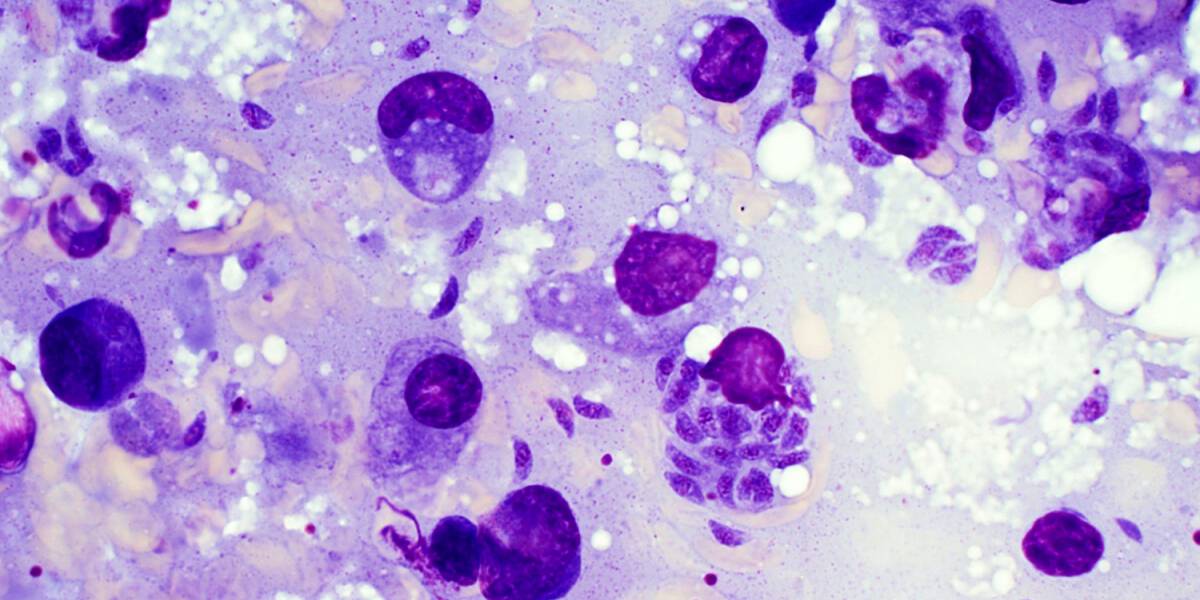

Toxoplasma Gondii

- Group: Apicomplexan

Perhaps the most notable of all body-snatching parasites, the Toxoplasma Gondii is a well-known brain parasite mostly found in rats. Once a rat is infected by this parasite, it is capable of manipulating and forcing the rat to do whatever it wants. In fact, many are trying to move around to different hosts. As a result, it will push for the rat to be seen by other animals. In particular, its most notable enemy, the house cat. Thus, the rat will go literally right at the cat rather than running away as it normally would. In fact, in one study, it was found that infected rats seem to be attracted to the smell of cats overall, but in particular their urine.

Now that the rat is more often than not killed by the cat, the parasite will now move inside the cat. This gives the parasite the proper room it needs to breed and further expand. There are quite a few cases of humans getting this parasite inside of them too. It is quite likely that they might have gotten it from their own cat. It is estimated that at least 60 million Americans have come in contact with Toxoplasma Gondii. That is pretty significant when you think about how hard it is for humans to randomly get parasites. At least those of us who understand hygiene. In humans, it could likely affect our brains and heavily reproduce if we do not kill it soon.

Sources:

National Institutes of Health

Centers for Disease Control & Prevention (CDC)

University of Minnesota

University of California, Berkeley

National Geographic

Journal of Crustacean Biology

Natural History Museum

University of California