Human activity is altering the world, including the lives of animals, plants, fruits, and vegetables. Our rapid growth, population rate, and technology have unintentionally changed the planet. Fruits and vegetables have been drastically transformed from their original forms due to human intervention, resulting in the development of modern crops with desirable genes for taste, looks, and disease resistance. Genetic modification has also played a role in enhancing the quality and quantity of produce. Despite the changes, we can appreciate the flavors and diversity of the fruits and vegetables we enjoy today.

Mangoes

The mango, first harvested in India over 4,000 years ago, has since spread throughout the tropics and warm subtropics, with different effects on its genetic structure and diversity depending on its migration direction. The mango’s journey westward through Africa and on to the Americas experienced population bottlenecks, limiting the genetic diversity that reached the New World. In contrast, eastward expansion into Southeast Asia brought the mango into contact with numerous other Mangifera species, promoting genetic diversity. Human intervention has altered the mango’s size, shape, and taste, resulting in a supersized fruit with delicious juice that drips down one’s chin with every bite. (Ranker)

Apples

Around 7,000 years ago, humans swooped in and changed the history of apples. Without human interference, humans likely wouldn’t want to eat apples. They were smaller and more bitter than their counterparts today. According to News, researchers “found that cultivated apples were 3.6 times heavier, about half as acidic, and far less bitter than the wild species from which they are derived.” A bitter, smaller apple doesn’t sound appealing. The sweet goodness that we bite into today sounds a lot more pleasant. They also found that by “using historical records, we found that apple breeding over the past 200 years has resulted in a trend towards apples that have higher soluble solids, are less bitter, and soften less during storage.” If humans opened their fridges nowadays to a soft, moldy apple, we don’t think the grocery stores would make much of a profit from selling them.

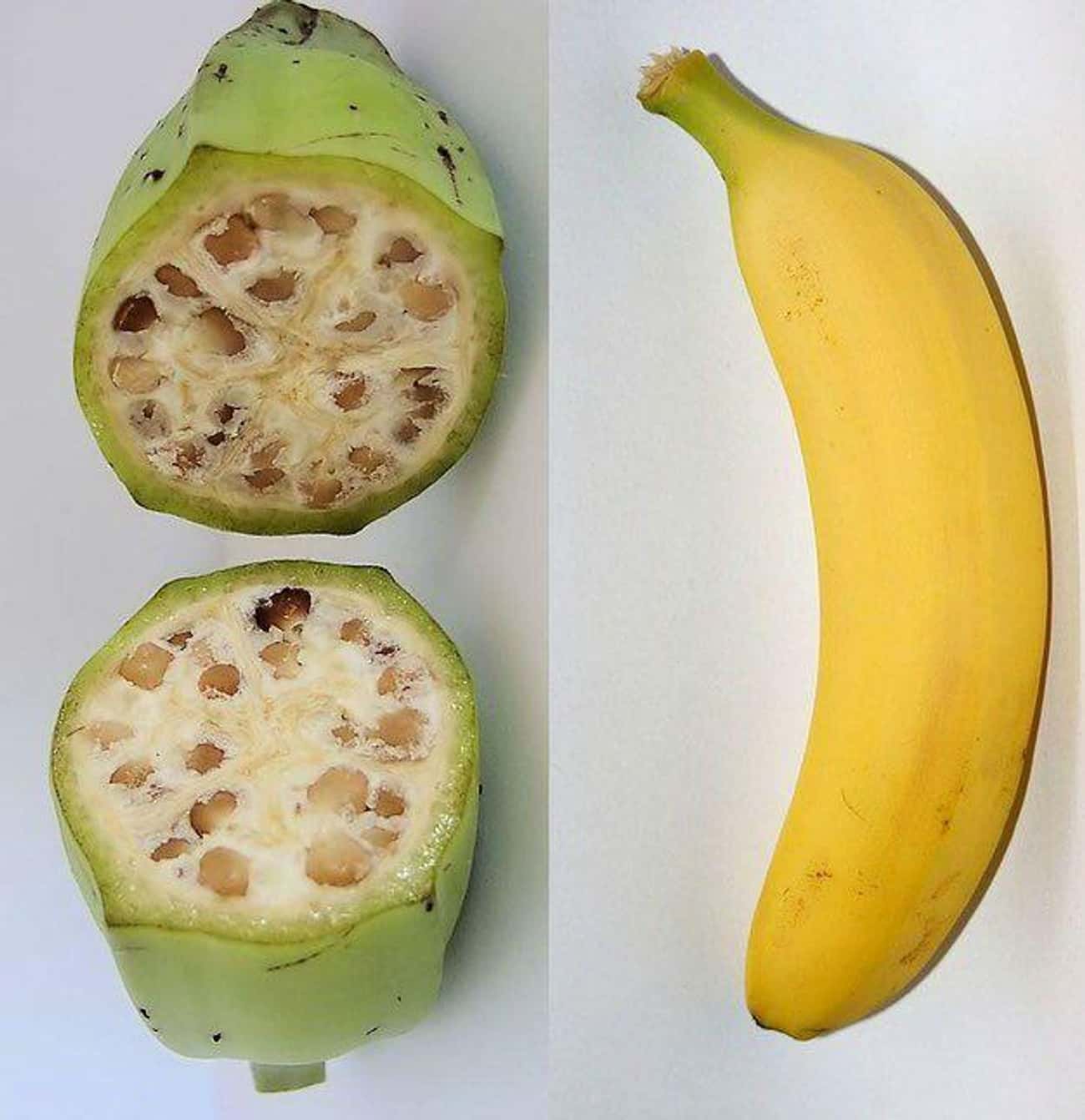

Bananas

Believe it or not, banana cultivation precedes the cultivation of rice. That’s right, we were changing bananas way before we were changing rice, one of the most ancient foods in the world. It’s said humans cultivated bananas in Papua New Guinea at least 7,000 years ago, and possibly up to 10,000 years ago. It’s said that “early bananas were green or red, and were prepared using a variety of cooking methods. The original bananas could only be eaten after cooking, which is contrary to the bananas we eat raw today. The current yellow sweet banana is a mutant of the plantain.” Mutant plantains? Sign us up! Before human interference, bananas had large, hard seeds. We weren’t able to sit back and peel a banana with the ease we can nowadays. Better yet, modern bananas have way more nutrition than their ancestors, including potassium, Vitamin B6, and Manganese (Business Insider).

Kale

Humans originally cultivated kale in the Mediterranean. Before human interference, though, kale was a lot less nutritious. Nowadays, it’s leafier, when previously it looked like a normal plant you’d find in your backyard. According to Frontiers In, “the domestication syndrome of kale includes apical dominance, ornate leaf patterns, the capacity to delay flower formation and maintain a vegetative state producing a higher yield of the edible portion, the nutritional value of leaves, and the ability to defend against herbivores that also give the leaves a unique pungent taste.” Luckily for us kale lovers, there are a lot more edible parts nowadays that we can eat, including the leaves and stems.

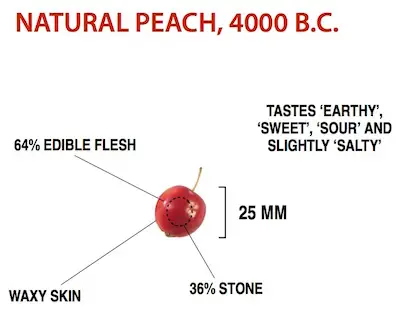

Peach

Originally, peaches used to be small, cherry-like fruits with a tiny bit of flesh. The ancient Chinese first domesticated them around 4,000 B.C. They tasted earthy and slightly salty. Peaches are now 64 times larger than their counterparts, 27% juicier, and 4% sweeter. If one of those new-age people complains that we’re eating genetically modified food, hand them a peach and tell them we already are. Wild peaches and cultivated peaches have very different flesh, too. After digging around a bit, researchers found that “wild peaches tended to have thin, tough, flesh. Cultivated peaches are larger and have a greater volume of flesh in proportion to the stone. Modern varieties also have a wider range of maturity times than wild peaches, allowing for a supply of fruit over a longer period.” The ones you find at the grocery store are sweeter and juicer than their wild counterparts.

Corn

After the viral TikTok video with Tariq the corn kid, we’ll never think of corn the same way again. But way before the video went viral, corn was popular. The entire world eats this vegetable. A variety of recipes use corn. The most iconic human interference in regards to corn is the North American sweetcorn, which was “bred from the barely edible teosinte plant. Natural corn, shown here, was first domesticated in 7,000 BC and was dry like a raw potato. Today, corn is 1,000 times larger than it was 9,000 years ago and much easier to peel and grow.” Sugar makes up 6.6% of corn and 1.9% of natural corn. Ever since the 15th century, when the European settlers came in, the life of corn changed. Now, we enjoy it roasted on a barbecue.

Guava

Nearly 5,000 years ago, humans cultivated the guava fruit. It was called the Psidium dumetorum and is a part of the Myrtaceae family, endemic to Jamaica. Researchers recorded the last plant in 1976 in a streamside thicket in Clarendon, Jamaica. Researchers consider it extinct. The original guava plant was a pest that dominated all the other plants. It was called the strawberry guava, and it “grew across hundreds of thousands of acres of native forest, clearing out practically every other plant in its path” (Daily). Guava plants today aren’t so invasive, and the strawberry-pear hybrid is sweet and pleasant to eat.

Strawberries

What’s summer without delicious strawberries? We eat them in ice cream, on smoothie bowls, and cut them up for our margaritas. But strawberries weren’t always the sweet, rosy red fruits we now know. Before human interference, they were a lot more different. Previously, “the fruit was sourced from wild strawberries and some cultivated selections from wild species. The fruit appeared in ancient Roman literature for its medicinal use.” In the 14th century, the French transplanted strawberries from the forest to the gardens for harvesting. Back then, wild strawberries were smaller and spiker and eaten in smaller quantities. They were also lacking in taste. Eating a pie with this kind of fruit doesn’t sound appetizing at all.

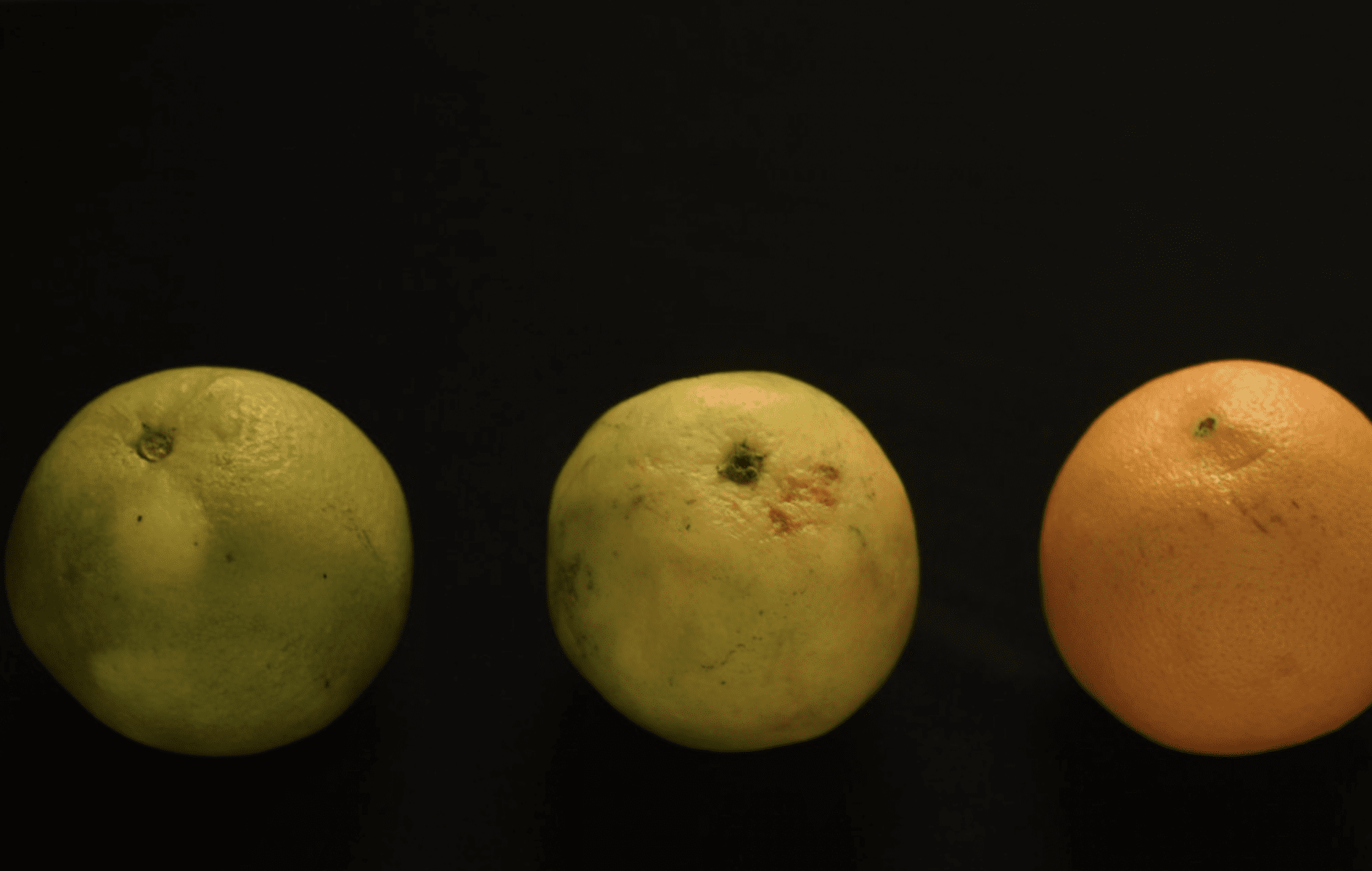

Orange

The original orange was not palpable, and clearly the complete opposite than the orange fruits we have today. Herbalists used it to make medicinal syrup. It wasn’t the delicious, citrusy fruit we bite into on a hot summer’s day. Like all citrus fruits, oranges originated in the foothills of the Southeast Himalayas. “A fossil specimen from the late Miocene epoch (11.6 – 5.3 million years ago) from Lincang in Yunnan, China has traits that are characteristic of current major citrus groups and provides evidence for the existence of a common Citrus ancestor within the Yunnan province approximately 8 million years ago (Story Maps). While it didn’t look very different than the wrinkly, old oranges we see today, it certainly tasted different.

Celery

Celery must be one of the most lackluster vegetables out there, considering its lack of taste and abundant flavor that many other vegetables have. But that doesn’t mean it doesn’t have many uses. Actually, “the fibrous plant has featured in Mediterranean and East Asian civilizations for thousands of years.” Many theories also “suggested that humans were transporting celery seeds as early as 4,000 B.C. Another variety of celery called “smallage” was present in China as early as the 5th century. The strong aroma may have boosted the appeal of the varieties in the Mediterranean and Asia.” Compared to celery back then, celery nowadays has thicker stalks. People consuming Water hemlock, a member of the celery family, used to die. Luckily for us, celery is safe to consume. As long as you wash the dirt off.

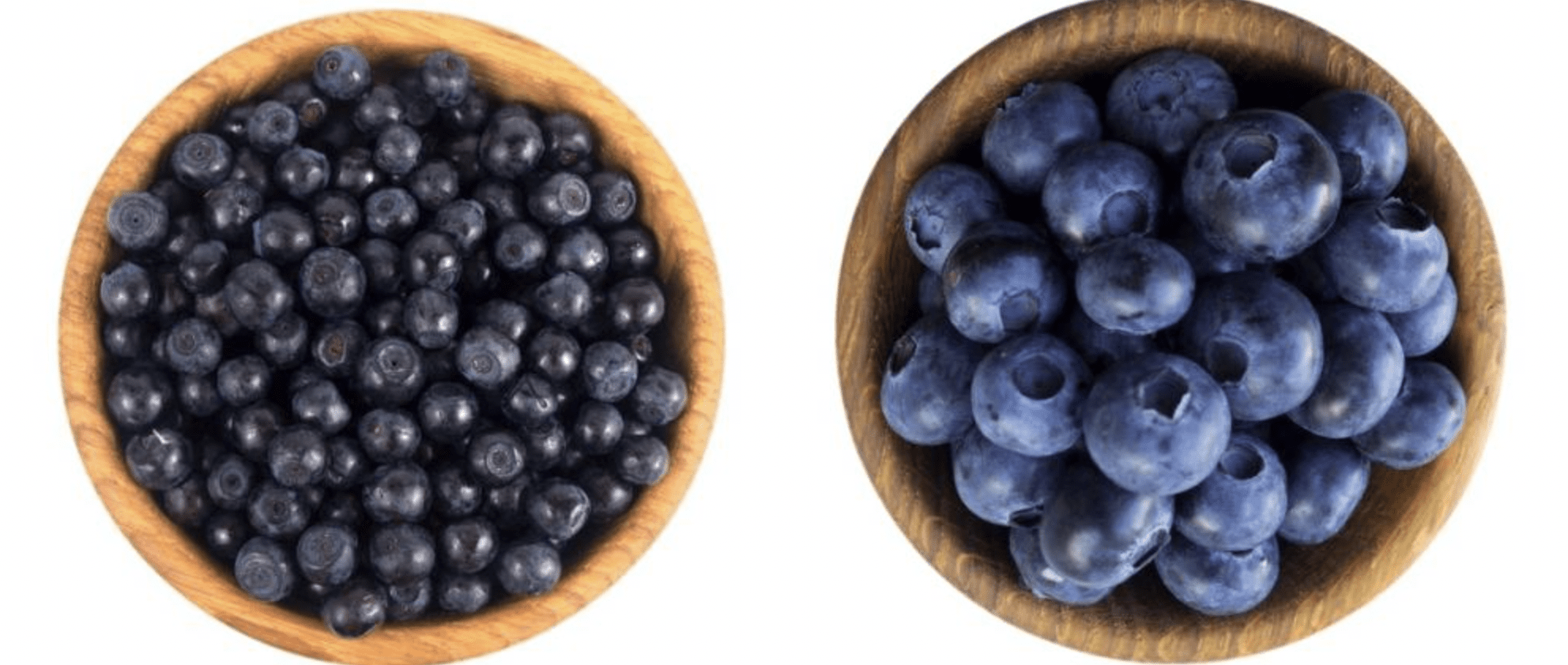

Blueberries

13,000 years ago, blueberries blessed the earth with their sweet, floral taste. In the 1900s, farmers cultivated blueberries. The blueberries that we eat today are a result of selective breeding by humans. Early blueberries were smaller, less plump, and less sweet than modern blueberries. Wild blueberries were first domesticated by Native Americans in North America over 13,000 years ago. However, it was not until the early 20th century that cultivated blueberries were developed, which were larger and more flavorful than their wild counterparts. (Ranker)

Pears

Originally described as “gifts from the Gods,” the early Romans developed pears and cultivated them into their juicy, sweet flavor. They can live to be 100 years old. The pears we see today are very similar to their ancient counterparts. Their buttery texture has withstood the test of time. There is one variety of pear, though, that’s extinct, and they’re called the Ansault pears. They became “extinct fruits because they weren’t reliable growers. Trees were irregular and didn’t always produce edible pears.” Then, commercial farming industrialized. Farmers didn’t receive a steady income from the unreliable Ansault pear trees. Eventually, reliable pears replaced the Ansault pear species. The Ansault pears may live somewhere in the world without our knowledge.

Lemons

Around eight million years ago, the first citrus trees popped onto the planet. According to DNA evidence, we can trace citrus trees to the foothills of the Himalayas. Archaeological evidence attests that lemons have been cultivated for over 4,000 years, and were brought out of Asia sometime near the 200 BCE where they are said to have been used in Israel as part of Jewish rituals. By 200 AD, traders had brought lemons to northern Italy. This is where they became popular among the Roman elite. Early lemons were smaller and less juicy than modern lemons, and they had a thicker skin and fewer seeds. Over time, selective breeding by humans has led to the development of larger, juicier, and seedless lemons that are more palatable and easier to consume. Additionally, the introduction of lemons to different regions of the world has resulted in the development of unique lemon varieties with distinct flavors and characteristics. Today, lemons are widely used in cooking, baking, and as a source of Vitamin C, and they continue to be selectively bred and improved by humans.

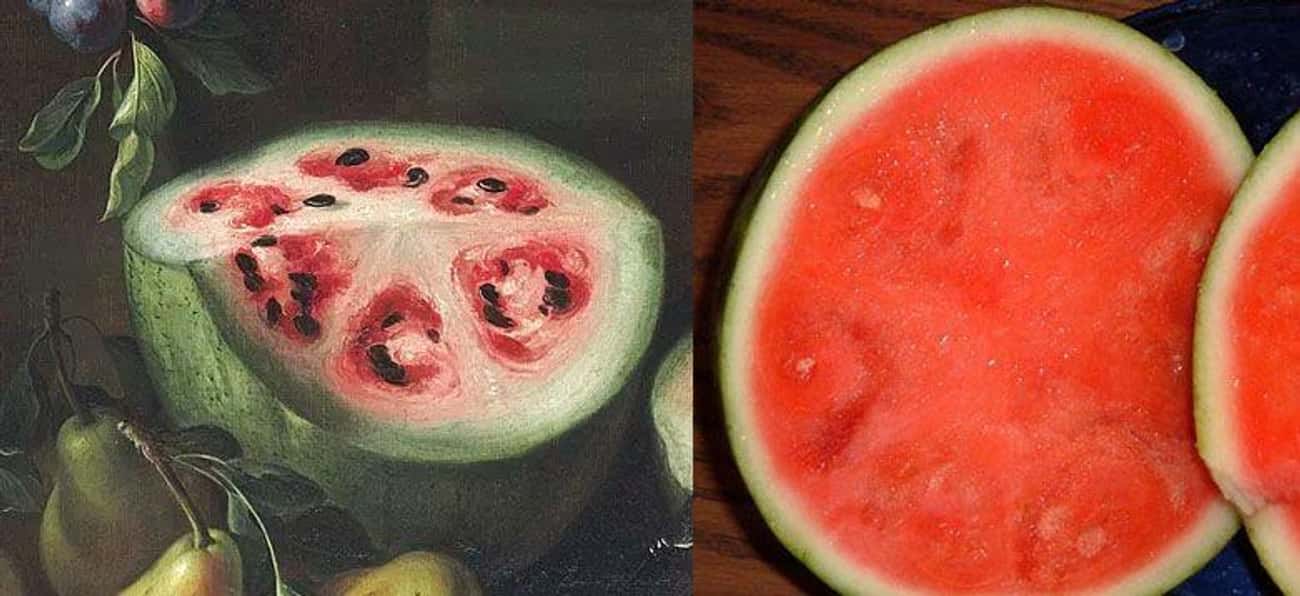

Watermelons

Watermelons weren’t always as beautiful as they are today, though they’re one of the most hydrating fruits in the world. If we take a step back and look at the history of the watermelon, a “17th-century painting by Giovanni Stanchi depicts a watermelon that looks strikingly different from modern melons.” The painting dates back between 1645 and 1672. The cross-section showed “swirly shapes embedded in six triangular pie-shaped pieces.” Over time, humans bred watermelons to have a red, fleshy interior, which is the placenta. Even though watermelon seeds “boost immunity and heart health and help to control blood sugar levels,” we wouldn’t want to eat that many seeds. We’re happy with the human interference on this one.

Wild Potatoes

French fries wouldn’t be the same without the cultivation of the wild potato. We just wouldn’t have French fries. That’s a life we don’t want to know about. Potatoes weren’t always this delicious, they used to be a lot smaller before human interference. NHM reports that the original wild potatoes, seen in Europe, had small tubers the size of cherries or peas. The length of the day regulated the tuber’s size. The potatoes grew close to the equator in the Andes, with equal days and nights. Eventually, humans cultivated potatoes to have larger tubers than humans eat today.

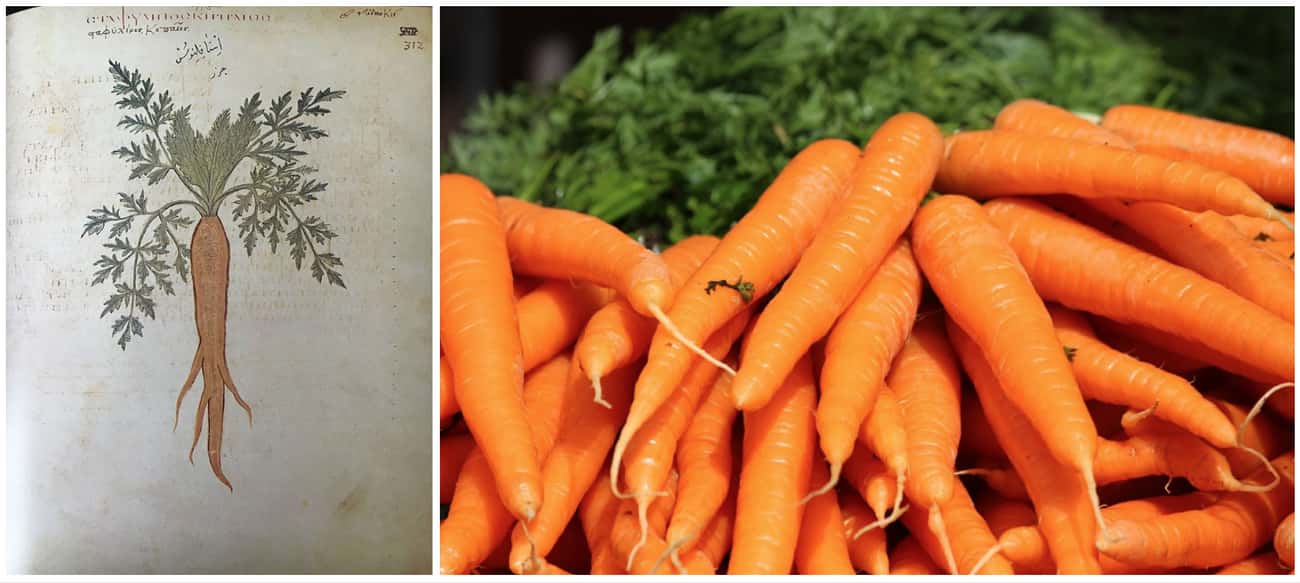

Carrots

Before human interference, carrots took two years to grow. and they were purple with a strong flavor. Eventually, they developed a blue color which turned yellow. Farmers in the 10th century began growing carrots in Persia and Asia Minor. Carrots had a white or purple color, and the thin forked root slowly developed over time. They also had a strong flavor and biennial flower, and after human interference, they became the large, tasty, flavorful orange winter crops we eat today. Carrots are delicious vegetables used in stews, wraps, curries, and chili (Business Insider).

Peas

Our Neanderthal ancestors ate peas about 23,000 years ago. But it wasn’t until 11,000 years ago that human interference made them into what we see today. Before cultivation, peas likely had a harder shell. When humans came in and interfered, we created peas with softer shells that could ripen during the rainy season. Nowadays, “wild peas put out seeds all over their flexible plant stems, and they have a hard, water-impermeable shell that allows them to ripen over a very long period.” Peas are used in a variety of dishes, including pasta, purees, and processed meat. It’s a good thing humans cultivated this starchy vegetable.

Eggplant

Eggplant, also called aubergine, come in all sorts of shapes and sizes. Mostly, we know them as purple, but they’re also blue, white, and yellow. But, the Chinese cultivated some of the earliest eggplants. “Primitive versions used to have spines on the place where the plant’s stem connects to the flowers. But selective breeding has gotten rid of the spines and given us the larger, familiar, oblong purple vegetable you find in most grocery stores” (Business Insider). Explorers in the New World tried to introduce the eggplant in the 1500s, but it didn’t catch on until much later. It wasn’t until the 1960’s when the smaller varieties in Japan came to America, and they’ve only recently adopted the Indian, Japanese, and Chinese eggplant varieties. These might be some of the youngest vegetables in the states.

Avocados

Before human interference, avocados were much smaller. They had larger pits and rotted faster than they do today, which seems impossible considering they seem to go from rock hard to rotting within a day or two. Americans ate two billion pounds of avocados last year, so it’s a good thing humans came in and changed the trajectory of the avocado. Avocados were originally from Mexico, and humans started eating them 10,000 years ago, and it’s said they’re as old as the wheel. Spanish explorers discovered the fruit (yes, an avocado is a fruit) in the 16th century, and by 1521, it spread into Central and South America (Ranker).

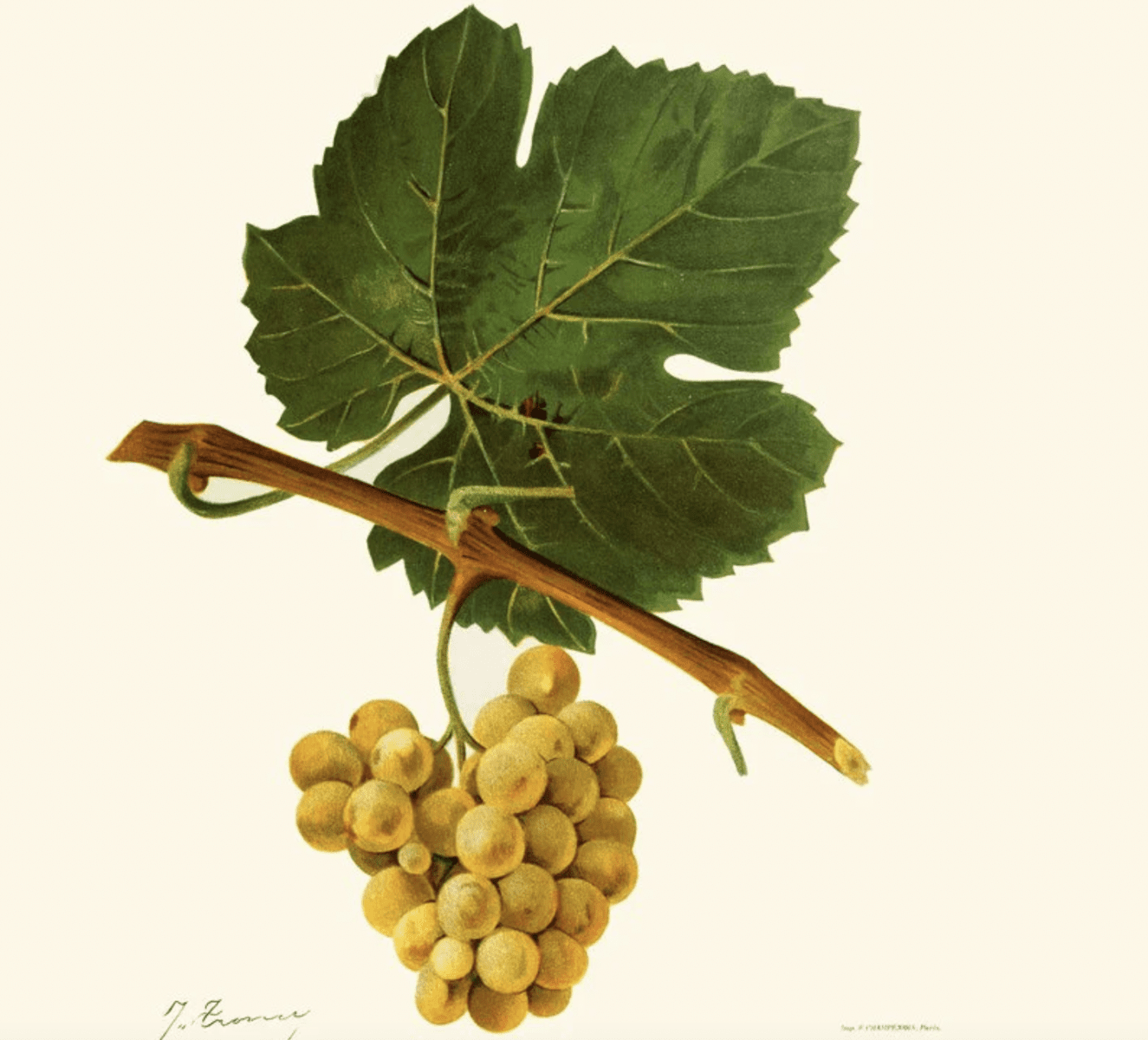

Grapes

Grapes dating back centuries tasted much like the wine grapes we have today. “Researchers conducted DNA tests on 28 samples of grape seeds dug out of waterlogged wells, dumps, and ditches at archaeological sites across France. The results, published today in the journal Nature Plants, show strong connections between modern wine grapes and those used as far back as the Roman period.” The DNA between modern grapes and ancient grapes is technically very similar. We’ll never truly know if the wine we sip on today is the same wine that sloshed around our ancestor’s wooden chalices. But it’s safe to assume it’s a bit similar.

Cucumbers

You’ll find cucumbers, the long, green fruit, in alcoholic beverages on the beach or in a mound of salad. Before human interference, they were smaller and spikey. They originated in India and humans cultivated them for at least 3,000 years. In the 9th century, records showed it arrived in France and England in the 14th century. According to the Canadian Encylopedia, the “cucumber is low in vitamins, has a mineral composition comparable to tomato, is rich in water, and has practically no calories.” Even though it’s lacking nutrition, it does taste great in a variety of dishes. Three hundred years ago, English people referred to cucumbers as “cowcumbers.” And, Emporer Tiberius of Rome ate cucumbers every day, so it comes as no surprise that they’re still a popular fruit today.

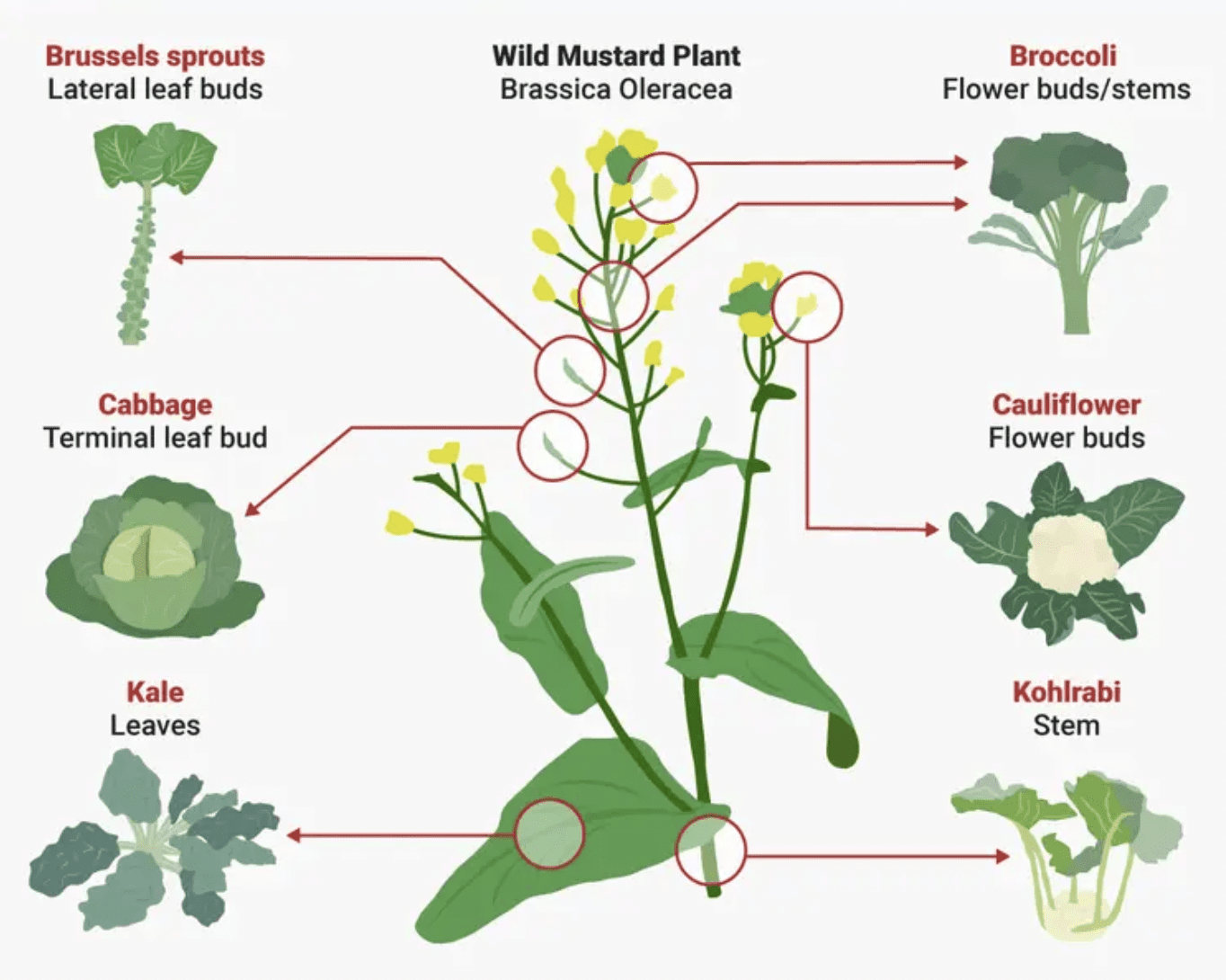

Cabbage, Kale, Cauliflower, Broccoli

Kale, sprouts, broccoli, and cauliflower all come from the same plant, Brassica oleracea. Scientists specifically cultivated it to create those green leafy vegetables we munch on our dinner plates today. Humans used those leaves and cultivated vegetables like broccoli and cauliflower. Humans genetically modified cabbage “by selecting a short petiole and evolving it over time,” and it was bred to have a more appealing taste and flavor to humans. It was first domesticated in Western Europe, and today’s cabbage is extra leafy compared to its less-leafy ancestors. This dates back about 10,000 years, and modern technology allows us to cultivate broccoli with higher levels of phytonutrients.

Plums

Before human interference, plums were smaller. They were closer in size to grapes, as opposed to what they’re closer to today, which is apples. It’s said that plum fruits may have been one of the first fruits domesticated by humans. According to Prime Scholars, “plum remains have been found in Neolithic age archaeological sites along with olives, grapes, and figs.” Humans cultivate plums in all temperate climate countries of the world. These Neolithic plums weren’t the plums we see today. There is one plum that hasn’t made it to modern days, and that’s Murray’s plum. It is scientifically known as Prunus murrayana and was found in Texas at the Edwards Plateau in 1928. No one has seen it since then, but if you’re feeling adventurous, go ahead and look for a thorny shrub 17 feet tall, with white flowers and red plums with white dots. A little bit of detective work never hurt!

Almonds

The history of almonds is a prime example of how human interference can change the course of evolution for a particular species. It’s fascinating to think that what we now know as a healthy, delicious snack once had the potential to be deadly. For hundreds of years, almonds were bitter and full of cyanide, a deadly poison that could kill you. The reason for this bitter taste was a compound called amygdalin. However, humans eventually discovered that almonds could be made edible by roasting them. Roasting removes the cyanide-producing compound and enhances the nutty flavor. This led to the domestication of the almond tree, as people started to cultivate it for consumption. Over time, almond trees underwent genetic mutations that eliminated the cyanide gene, making them safe for human consumption even in their raw form. Humans also began to selectively breed almond trees for sweeter and larger nuts, leading to the development of different varieties of almonds.